Ah, telephemera… those shows whose stay with us was tantalisingly brief, snatched away before their time, and sometimes with good cause. They hit the schedules alongside established shows, hoping for a long run, but it’s not always to be, and for every Street Hawk there’s two Manimals. But here at STARBURST we celebrate their existence and mourn their departure, drilling down into the new season’s entertainment with equal opportunities square eyes… these are The Telephemera Years!

Pre-1965, part 4: 1963-64

There’s no concrete reason why The Telephemera Years begins in 1965, except for arbitrary reasons of available content and the more solid fixed point that is the great colour transference of that year, when it was announced that half of all network programming would be broadcast in colour from the Fall 1965 season. The years before we were gifted My Mother the Car, Lost in Space, and (eventually) Batman may look thinner in terms of genre programming but there were still those hardy souls doing pioneering work in the field of the strange and the fantastic.

So, while The Beverly Hillbillies, Bonanza, Gunsmoke, and Wagon Train dominated the ratings, less rustic thrills could still be found dotted across the schedules, right up to a 1964 Fall season which saw The Addams Family, Bewitched, Flipper, Gilligan’s Island, Jonny Quest , The Man from UNCLE, The Munsters, and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea all make their TV debuts. So sit back, pop on your slippers and light up your pipe, have the little lady bring you a little treat, and see what the pre-1965 era has in store for us…

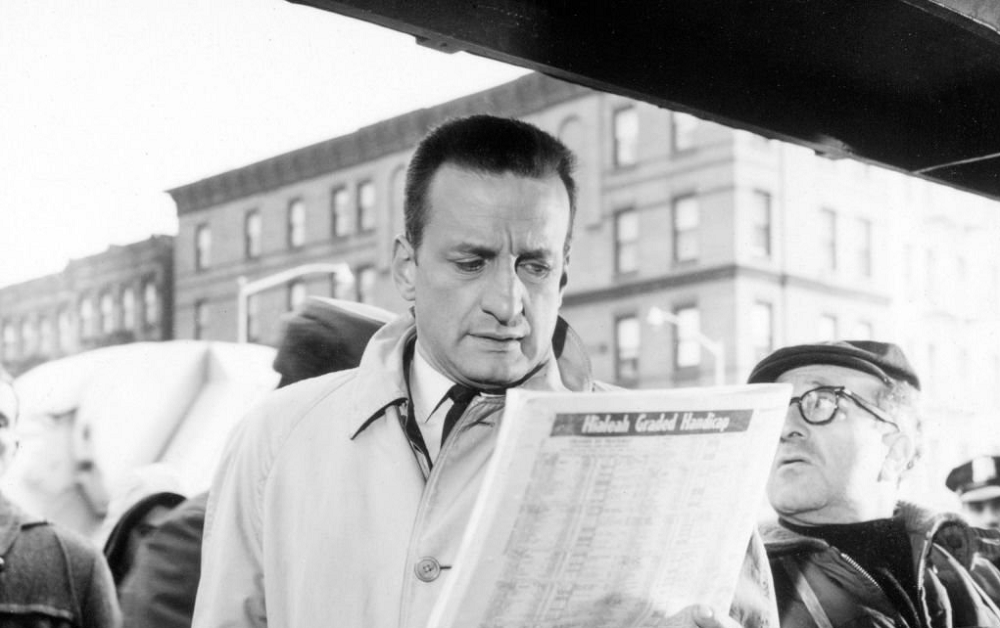

East Side/West Side (1963, CBS): David Susskind is not a name spoken of often when the history of television and civil rights is told and it’s an unfortunate oversight that ought to be corrected at every opportunity. A working-class Jew from Massachusetts, Susskind graduated from Harvard in 1942 and, after serving in the US Navy during World War Two, became a talent agent for Warner Brothers, ultimately forming his own agency – Talent Associates – to represent those involved in television and film production.

In 1958, Susskind stepped in front of the camera to present Open End, a talk show that aired on New York commercial station WNTA. Three years later, the show was renamed The David Susskind Show and went into national syndication, bringing Susskind’s frank and open discussion to the American people. Alongside supporting Black emancipation and criticising the government’s foreign policy, Susskind was among the first to champion gay rights, giving a platform to those wishing to advance the cause, and even addressed transgender issues with a sensitivity and level-headedness that is lost on some even to this day.

Susskind also produced TV drama and East Side/West Side was an attempt to tell the story of the New York he knew, highlighting the uncanny strengths of its people in the face of obstacles that were often institutional in nature. George C Scott starred as Neil Brock, a social worker working for a private agency who took cases others blanched at. The first two episodes alone dealt with prostitution and statutory rape, and subsequent cases involved PTSD, intellectual disability, gambling, mental health, and race, with no topic seemingly off-limits to Susskind and his team of writers.

The series switched tracks for its last five episodes, with Brock taking a job as an aide to a campaigning congressman, allowing the show to dip its toes into the rotten democratic process without ignoring ground-level issues. All this came at a price as sponsors avoided the show and many CBS affiliates declined to pick up the series, with one episode being blacked out in Louisiana and Alabama when it hit too near to home on racial discrimination. Despite a campaign by Susskind to earn a renewal, East Side/West Side was cancelled after just twenty-six episodes, but Susskind kept up the good fight through his other projects, with The David Susskind Show running until 1986.

Arrest and Trial (1963, ABC): When it arrived on our screens in 1990, Law & Order was hailed as new and innovative, dedicated as it was to showing the investigation and then prosecution of crimes in New York City. There are seldom any genuinely new ideas in television, however, and Earl Bellamy must have raised at least an eyebrow when Dick Wolf’s “new” show debuted on NBC…

Twenty-seven years earlier, Rosenberg had created Arrest and Trial, starring Ben Gazarra and Roger Perry as a pair of Los Angeles cops who would investigate the crime of the week during the first half of the ninety-minute show. The focus would then switch to Chuck Connors’s public defender, going head-to-head with the Deputy District Attorney in an attempt to find his client innocent of all charges, or at least mitigate on their behalf.

It was this crucial difference that gave Arrest and Trial its heart, coupled with Gazarra’s insistence that its depiction of the police not be stereotypical or hard-nosed, his Detective Sergeant Nick Anderson more concerned with what led to the crime being committed than how to punish the offender. Each week, a seemingly open-and-shut case would unravel, revealing depth and nuance not present in many other legal dramas.

In different hands, Arrest and Trial might have lasted longer than its thirty episodes and enjoy a more prominent place in TV history (Wolf claimed he’d never heard of the show when he created Law & Order) but executive producer Frank Rosenberg reportedly ignored commissioned scripts by writers he’d fallen out with and butted heads with Connors over this and Rosenberg’s treatment of the crew. Lacklustre ratings and strife on set led to the show’s cancellation in September 1964, although it did become later the first US show to be aired on BBC2 in the UK.

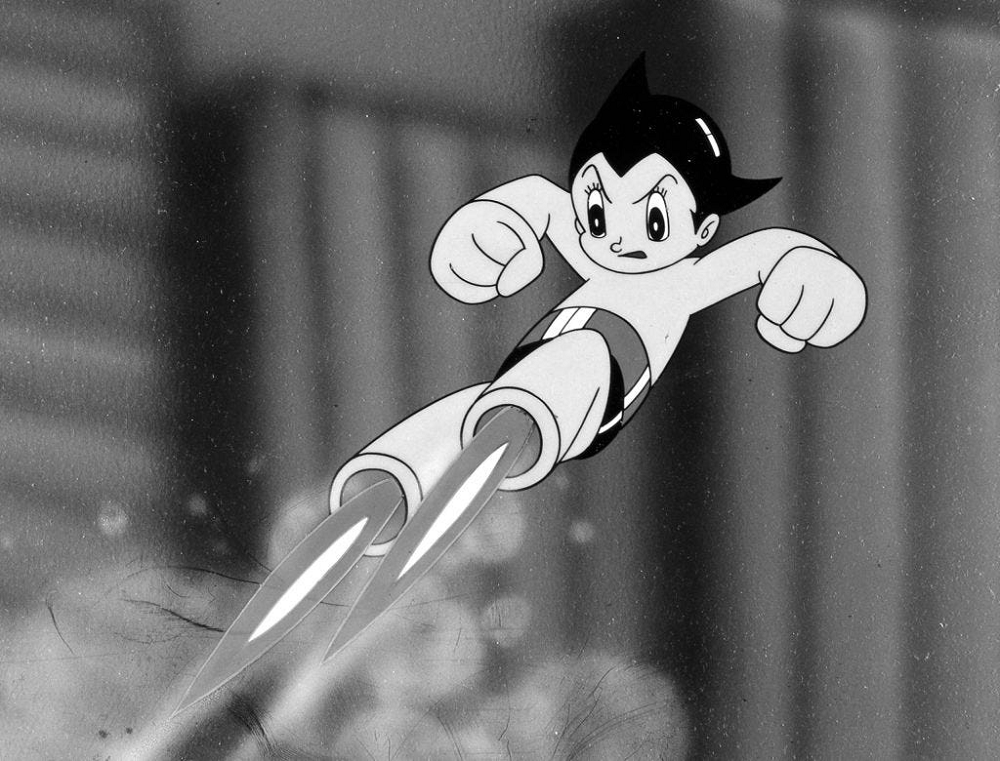

Astro Boy (1963, syndication): Osamu Tezuka is known as the “godfather of manga,” the Japanese comic book artform that earns far more respect than its western counterpart. In 1952, he created Tetsuwan Atom (“Iron-Armed Atom”) for serialisation in the monthly Shonen magazine, the story of an artificial boy created by a heartbroken scientist after the death of his own son. Astro Boy is soon sold to a robot circus but is rescued by a kindly professor who builds him a robot family and sends him off on adventures to better or save mankind.

Tetsuwan Atom became an instant sensation and when television ownership became widespread in the aftermath of the wedding of Prince Akihito, it was a shoo-in for a TV adaptation, a live-action version in 1959. That was short-lived but another version, this time animated, debuted in January 1963, originally adapted stories from the manga but soon outpacing the source material, leading to Tezuka providing original stories for the show. At its height, over forty percent of Japanese viewers were watching the show and its kid-friendly action and adventure themes made it a natural for overdubbing and airing in the US.

Renamed Astro Boy, the first episode premiered on NBC in September 1963, the first Japanese show to make it to US TV, and was initially very popular. Changes were made by the US network to tone down some of the content, which often angered Tezuka, but it was successful enough that NBC renewed the show after the first year of weekly episodes for a second run of fifty-two episodes. By the end of that run, however, ratings had declined to the point where the network declined to buy more, preferring instead to syndicate the 104 episodes they already had well into the 1970s.

In Japan, Tetsuwan Atom ran for 193 episodes, through to December 1966, and further adaptations were produced in 1980 and 2003. The impact of the show in the US created a nascent anime fandom that would explode as home video became more viable, and shows such as 8th Man, Kimba the White Lion, and Gigantor entertaining cereal-eating kids throughout the 1960s, with Speed Racer arriving in 1967 and becoming the next cultural save-point in the history of Japan-US relations.

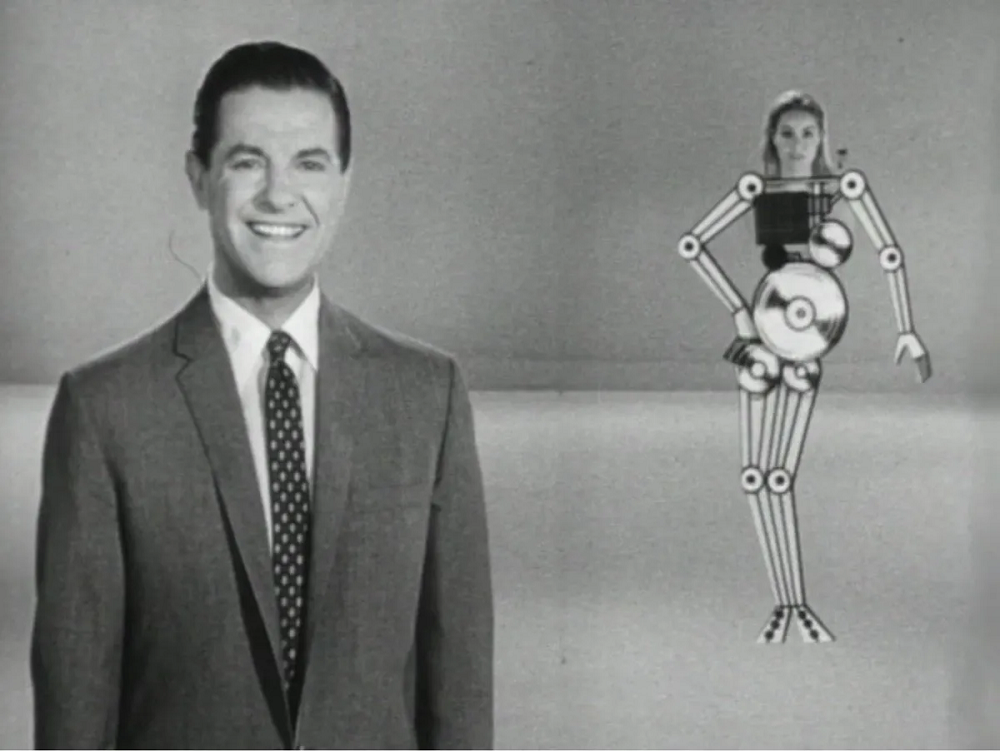

My Living Doll (1964, CBS): My Living Doll was created by Bill Kelsay and Al Martin, who had met while writing for My Favorite Martian. It was the success of that show that led to CBS ordering My Living Doll to series without even seeing a pilot, such was the pedigree of producer Jack Chertok, who had brought My Favorite Martian to CBS the year before and saw it become the number ten show for the season.

The living doll of the title was AF-709, a lifelike robot created by scientist Carl Miller for the US military but transferred into the care of psychiatrist Bob MacDonald (Bob Cummings) when Miller is transferred abroad and becomes worried what the military will do with his creation. MacDonald undertakes a mission to teach AF-709 – who Miller has named Rhoda – to be the perfect woman, although his idea of the perfect woman certainly doesn’t match the enlightened era of the 1960s, creating comedic tension between the developing Rhoda and her stuffy keeper.

The role of Rhoda went to Julie Newmar, a Broadway actress of statuesque proportions who had an otherworldly beauty deemed perfect for the part. My Living Doll was her breakout television role, earning her an Emmy nomination, although she is probably best known for playing Catwoman in the first two seasons of Batman, opposite Adam West and Burt Ward. She later returned to the theatre and was granted a patent for both pantyhose and brassiere developments.

My Living Doll was warmly received by those that saw it, who no doubt enjoyed its risqué nature and progressive humour, but they didn’t see it in enough numbers – it was scheduled opposite Bonanza and The Virginian, both huge hits – to save it from cancellation. Its lasting legacy, other than introducing the world to Newmar, is in Rhoda’s catchphrase, the first recorded use in popular culture of “Does not compute!”

Check out our other Telephemera articles:

The Telephemera Years: pre-1965 (part 1, 2, 3)

The Telephemera Years: 1966 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1967 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1968 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1969 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1971 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1973 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1975 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1977 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1978 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1980 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1982 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1984 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1986 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1987 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1989 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1990 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1992 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1995 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1997 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1998 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2000 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2003 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2005 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2006 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2008 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

Titans of Telephemera: Irwin Allen

Titans of Telephemera: Stephen J Cannell (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

Titans of Telephemera: DIC (part 1, 2)

Titans of Telephemera: Hanna-Barbera (part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Titans of Telephemera: Kenneth Johnson

Titans of Telephemera: Sid & Marty Krofft

Titans of Telephemera: Glen A Larson (part 1, 2, 3, 4)