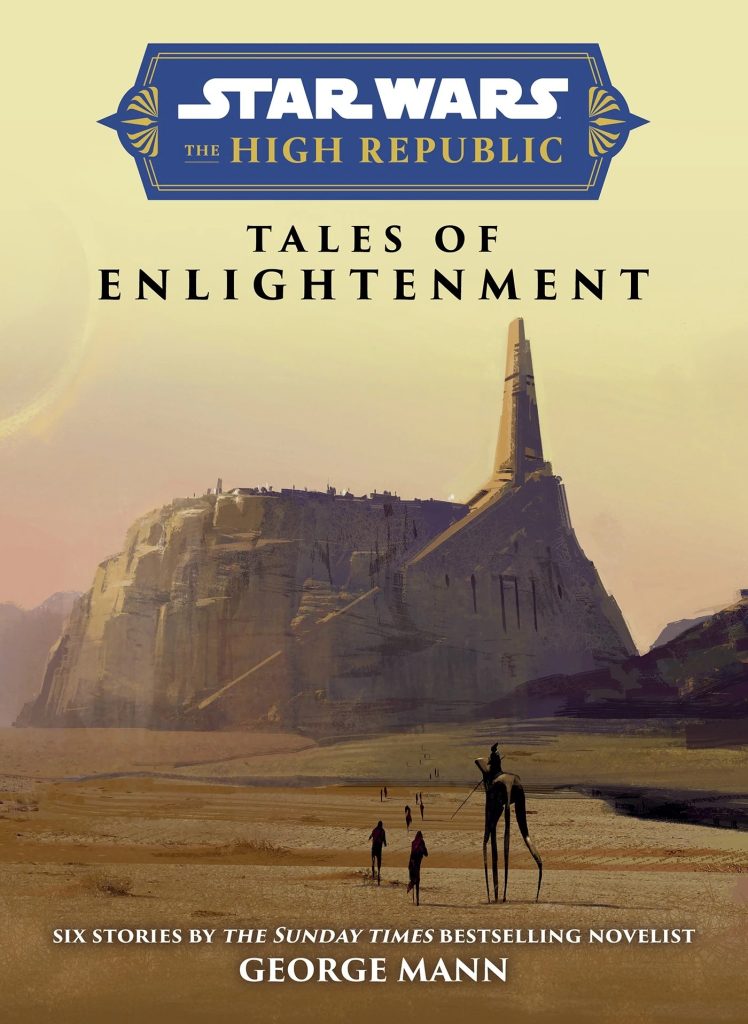

Out now from Titan Books, STAR WARS: THE HIGH REPUBLIC – TALES OF ENLIGHTENMENT is a brand-new anthology set in the galaxy far, far away. This special edition release contains six short tales, including a bonus story exclusive to the collection, as well as a complete guide to the award-winning second phase of THE HIGH REPUBLIC, and interviews with a selection of the authors. Here, TALES OF ENLIGHTENMENT’s author GEORGE MANN joins us to tell us about the anthology, his STAR WARS journey, and more….

STARBURST: Tales of Enlightenment takes place on Jedha – what made this iconic planet a good backdrop for this collection of Star Wars stories, and what kinds of characters will readers meet?

George Mann: Jedha is a writer’s dream of a Star Wars location. It’s a melting pot of Force-related faiths and sects, Jedi and non-Jedi, politics and peoples. There’s a huge amount of opportunity for storytelling and tension between different factions. In this era, it’s also a place where the Jedi aren’t quite as popular as they are around some other regions of the Republic. Here, they’re just another Force sect, and that, too, creates some interesting friction. Mostly, though, we chose Jedha as the location for these stories because of the huge, pivotal events that were happening there during Phase II of The High Republic storytelling. And we decided to set the stories in a tapbar [the titular ‘Enlightenment’] because it presented the chance to show the ground level view of local people of the events going on in the city, as well as being a great setup for having walk-on or guest characters appear in each story as they visit the bar.

You’ve been writing Star Wars since 2018’s short story collection Myths & Fables, can you remember how it was taking “your first steps into a larger world” – to paraphrase Obi-Wan; was it always a goal of yours to tell tales in the galaxy far, far away?

Yeah, it was pretty much a bucket-list gig. Star Wars has played such a part in my life, ever since I was a small child, and being able to contribute something meaningful to that story and galaxy is a real honour. I still pinch myself every time I have a character ignite their lightsaber when I’m writing!

How did the opportunity first come about?

Michael Siglain from Lucasfilm Publishing read one of my original novels and approached me about working on the Myths & Fables book. The novel I’d written featured a fictional mythology and I guess it showcased that aspect of my work. We had such fun working together on the first book that we did two more in the series, and it wasn’t long before I was invited to work on The High Republic project too. I owe Mike a lot for that initial approach!

At what stage were you first brought on board the High Republic team?

I joined the team towards the end of Phase I, when I wrote a Drengir-themed story for Star Wars: Dark Legends, and a couple of picture books for kids.

The stories featured in Tales of Enlightenment are all set during that era of Star Wars storytelling too; considering that the period has already produced 28 books and counting, is this anthology accessible to fans who might not have a deep knowledge of High Republic lore yet?

I believe so, yes. We try hard to make sure there are plenty of jumping on points to keep the stories accessible, and this collection is complete in and of itself, so readers can start and finish the story here. People should be able to pick up and enjoy these stories as they are.

When were you brought into the High Republic team, what characters stood out as favourites, and are there any who you’re still chomping at the bit to write about?

I do feel as though I’ve gotten to know a lot of these characters like old friends. I’d love to return to Silandra Sho and Rooper Nitani from Phase II. I had such fun developing those characters and I feel like there’s a lot of Pathfinder stories that could still be explored.

You’re an extraordinarily prolific author, having written countless – literally, we tried! – novels, comic books, screenplays, audiobooks, and non-fiction works since your debut in 2008. I guess our question is… how? What do your daily routines and disciplines look like in order to achieve such formidable output?

Technically, I debuted in 2000, but it wasn’t until 2008 that my first full-length novel appeared! I think the truth is that I like being busy, and I like working across different media. I try to keep my hand in across lots of different projects! I also try to keep office hours, but if I’m honest, it often spills into evenings and weekends too, particularly as I work a lot with people in different time zones. There’s no particular routine or anything – I just try to knuckle down and focus on what needs to be done. I always say writing a book is a bit like climbing a mountain – it’s about the day in, day out consistency, about always pushing forward. A novel is as much a test of endurance as anything else! What I love about writing scripts, be it comic, audio or screenplay, is the collaboration with other creatives. With a novel you tend to be working alone for long stretches and the end product is very much ‘you’. That can be very fulfilling. But at the same time, working with others means you’re often pleasantly surprised by the way things turn out, and the fact the actors or artists bring something new to the story is hugely exciting. So I try to get a good mix of different projects that I feel passionate about, some personal and some collaborative. Other than that, it’s just biscuits, tea and lots of hard work!

STAR WARS: THE HIGH REPUBLIC – TALES OF ENLIGHTENMENT is on sale from all good book shops, comic stores, and online NOW! And you can catch all-new and exclusive THE HIGH REPUBLIC – PHASE III stories in the current issues of STAR WARS INSIDER!