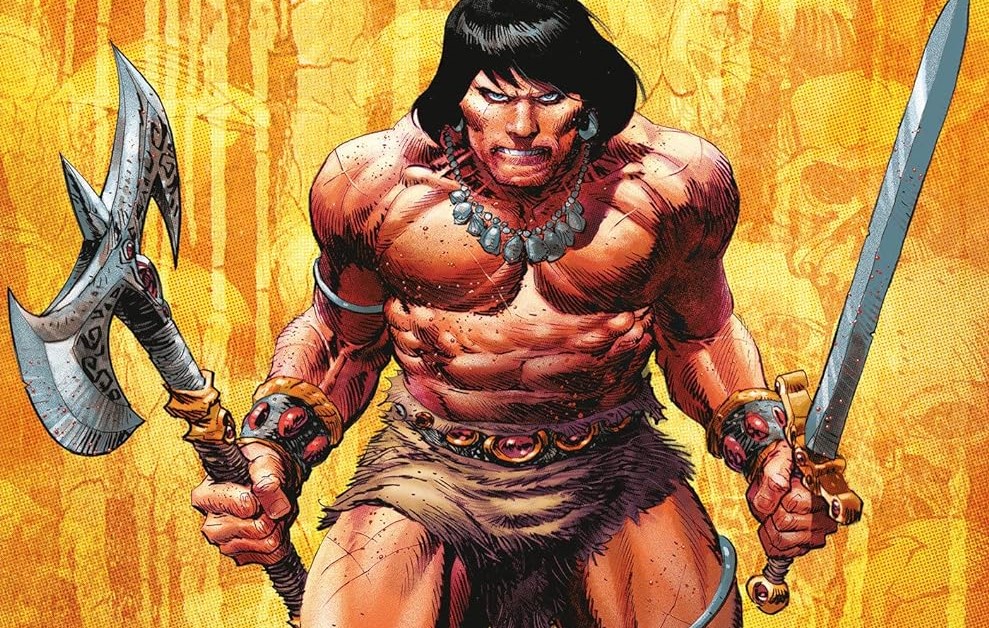

Conan the Barbarian may be a 90-year-old character, but that doesn’t for a moment mean he’s obsolete. The iconic pulp staple enjoys an ever-strengthening presence in comics, and film fans remember Arnold Schwarzenegger’s time with the character fondly. Now, Titan Comics is unleashing CONAN THE BARBARIAN: BOUND IN BLACK STONE, a sprawling epic charting the eponymous warrior’s adventures in monster-clogged locales. Co-leading the charge into Conan’s new ongoing series is writer JIM ZUB, whose knowledge and zeal make him a perfect fit for the project. A long-time comics scribe with a fierce love for pulp, Zub strives to do right by creator Robert E. Howard even as he strikes out to make his own mark on Conan canon…

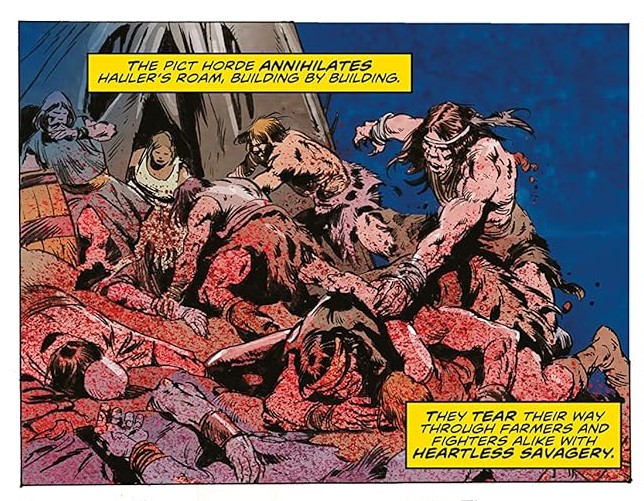

With Conan the Barbarian: Bound in Black Stone, Zub has teamed up with artist Rob De La Torre to revive the retro pulp spirit underpinning every Conan adventure. Zub’s accessible storytelling, coupled with art that would have John Buscema swelling at the seams, escalates everything fans already love about Howard’s world: satisfying beat-downs, bottomless mythopoeia, and vibrant characters who basically peel themselves off the page. STARBURST MAGAZINE recently caught up with Zub about Bound in Black Stone, Conan’s immortal appeal, and the breadth and depth of his mythology…

STARBURST: Tell us about your dynamic with artist Rob De La Torre. How do you guys complement each other as creators?

Jim Zub: Here’s the thing, Rob and I, we had been wanting to work together for quite some time, and being able to team up on this Titan relaunch was really a dream come true. So I’ll roll back a bit and explain a bit on that because I think that it informs a lot of the way that we’re working. Heroic Signatures and I had stayed in touch after the license wrapped up at Marvel and they wanted to take a different tack going forward with their publishing plan. They wanted to have a more direct hand. Rather than doing a licensing thing, they wanted to really be deeply involved in the creative aspect of publishing Conan going forward. The character has got a 50-year legacy in comics and a 90-year legacy in publishing. He’s one of the most important literary characters.

Huge!

He’s the Superman of sword and sorcery. And so they felt like they could do that and they found a partnership in Titan, and they had approached me because they really liked the voice that I had for the character previously, and they knew I had some pretty ambitious plans and ideas. I pitched them this longer term, big mythic structure that we could follow and ways that we could use the canon stories as pillars for future plans. And I felt like De La Torre’s art spoke to a classic era of the character, obviously, John Buscema and Frank Frazetta and his own artistry that he brings a really great pulp kind of aesthetic that we could convince readers that we had their backs, that we knew why they love this character and what was so special about it. And the more Rob and I talked about that, the more we also looked at even the working methodology that worked so well with those old comics.

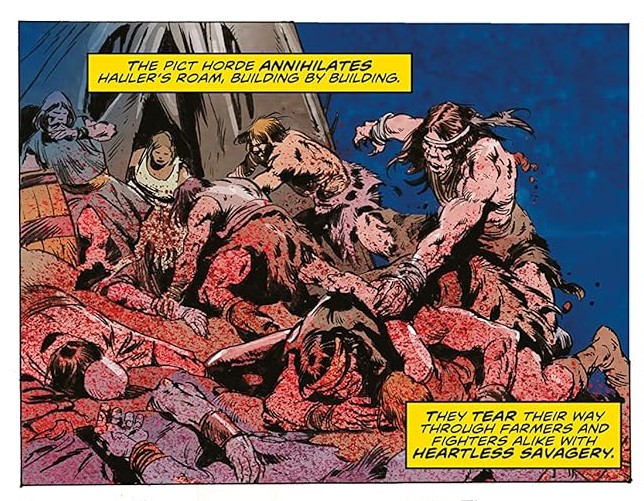

And so, Rob is a very complete artist package. So he and I spoke about working plot style like Roy Thomas and John Buscema did in the seventies. I’m laying out the big beats of the story in a plot manner. I’m describing big poetic moments and then letting him go buck on the page. Then I come back in and I dialogue it. So the reason why I think the text marries so well is because it’s being built with that specific page in mind. I am trying to summon the poetry to match his phenomenal vision of the Hyborian Age. And it is really a vision between him and Dean White and Jose Villarrubia, with the colours just enhancing it.

It feels like the best kind of throwback where it’s not like… It’s not homage in the sense that we’re tracing off that old thing or trying to just redo what’s been done before, but we’re trying to take the fuel, the reason why Conan was one of the bestselling books in the seventies and had consistently some of the highest subscriptions at Marvel in that period, both for Savage Sword in the monthly title and go, “Why? Why do people love it so much? What makes this character stick around so long and be so intrinsic to that broader pulp culture voice that it seems to have?” And put all of that on the page but try and move forward with new stories that can still surprise readers.

That’s that weird, crazy tightrope that we’re walking with this thing, than if it’s just a complete throwback, that it feels like everyone goes, “Well, I’ve seen this before. I know what comes next.” Then it’s forgettable. It just gets lumped in with existing material. And so, for us, it was like, “Okay, take the best stuff. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater and surge forward as much as we can with it.” And we knew we only had one shot at grabbing the old fan base and saying, “Remember how badass this was? Remember how amazing this was? Stick with us. We got a cool ride coming.”

The plot and the story, is that where you feel the concept is the most pliable in terms of trying to walk that tightrope between honouring what has been and then trying to create something new?

We’ve got two main advantages. We’ve got a big overplot that we can plan out over a longer period in a way that a monthly comic of the seventies didn’t have those kinds of benefits. You get the fidelity of modern printing and colour reproduction and stuff that we can do on a whole other level. And we can make it a mature reader’s book, the promise of the pulps in terms of being a bit of forbidden fruit in terms of violence and content that you just couldn’t get away with under the Comics Code Authority or even the black and white magazine. We can take things further in that respect. And so in that way, I think it updates that feeling, it makes a modern version, but trying to project it forward rather than feel embarrassed by the past, if you will.

It’s cool because Conan stirs nostalgia in us, creating this illusion that he was always part of our coming-of-age. Even, or especially, if we’re picking up his stories for the first time.

An icon. It created a publishing empire for the character that didn’t exist before beyond the Weird Tales readership, which was obviously substantial, but not like the Lancer paperbacks changed fantasy publishing. And that’s on the back of that vision of Frazetta and that grit of that character that he projected on those covers. And then you get artists like Barry Smith and John Buscema and just Ernie Chan and Alcala and all these other artists that brought that vision forward with the comics and with Joe Jusco and Boris Vallejo and all these guys. And so it’s this amazing legacy that we’re trying to capture and say, “Here are the coolest qualities or here is as much of that…” Acknowledging that stuff exists, but not getting ourselves so wound up in the minutiae that a new reader couldn’t dive in and just go, “What’s Conan all about?”

Conan is an adventurer with wanderlust and where he goes, incredible things will happen. Is there other stuff that you can know? Of course. There are periods of the character’s history. There is the geography of the Hyborian Age and there are cultures and interesting echoes of real world history, but all of that is bonus material. You don’t need to know any of that in order to pick up a book and enjoy. Conan is a survivor. He is a barbarian in a civilized kind of kingdoms, and the clashing of those concepts and the intrinsic themes of, you can trust a barbarian more than you can trust any kind of ‘civilized’ – and I use civilized with the hanging air quotes – and, because the act of running a kingdom and a government creates corruption. And this barbarian will kill you where you stand, but he’s going to tell it to your face. You know what I mean?

He demands honour from the people around him, too.

Right. And that’s a form of the author. Robert E. Howard grew up in rural Texas during the oil boom and saw these civilized structures corrupting and crushing and destroying, and he lusted after the idea of the frontier and the self-made man, and it’s very intrinsic into the writing and you see that survivalist mentality and explorer, adventurer sort of stuff that ignites his imagination and his ability to take a pretty… The pulps, which were very disposable kind of entertainment and try and forge a real poetry around it. There’s a reason why there’s only a handful of writers from that era that we still look at to this day. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft and a couple other contemporaries of that time, and it still works. You read those short stories and they are pure entertainment. They’re quick, they don’t waste time, they’re just intense from start to finish and it’s trying to summon that up on the printed page as much as possible. That’s the challenge and that’s what’s so exciting about it.

You can read Bound in Black Stone on its own. You don’t need to know anything else. And so I think, like you said, it is tailor-made to be enjoyed in the moment without prior knowledge.

There’s a procedural aspect to this kind of iconic character. What we’re most fascinated by is putting Conan into different situations and seeing how the character we know responds to it rather than, he doesn’t necessarily follow traditional character arcs where the character has to go through dramatic revelations. We have some of those elements. If you look at the longer progression of the character, whether it’s Conan in his impetuous youth testing his limits, Conan is his prime, realising he’s a veteran of many battles and a capable leader, and then being pulled into becoming a king by his own hand and realising that he has to somehow become a king and not lose his soul, not lose the thing that made him vibrant. And can anyone do that once they’re past their prime? That’s the big question. So there is a broader arc, but you can drop into a story at any point and just go, “Oh, this is Conan in this period!”

The fandom doesn’t seem toxic at all.

Yeah, that’s really exciting about it. And so within my stories, we’re forging certain types of continuity and callbacks and we’re utilising the pillars of the canon in hopefully ways that readers haven’t quite seen before. The other thing that we have to our advantage is, although there are these twenty-odd Conan stories, he wrote hundreds of pulp stories and many of them, whether it was for expediency or whether it was with this idea of continuity, call to each other. The Thurian age of Kull the Conqueror is the pre-history of the Hyborian Age. And it isn’t just because of fan theories. That is nailed down in the texts. There are callbacks and there are tethers between them. But then other stories that Robert E. Howard wrote have those tethers as well. There’s a story, there’s these two characters called Kirowan and Conrad, and they’re kind of pulp investigators, scholars of the occult, and one of the stories that they have, the Haunter of the Ring, they find the ring of Thoth-Amon. That’s in Howard’s pulp stories, and Thoth-Amon is a villain from the Conan stories. That’s not just us blowing smoke, that’s in the actual text.

And that kind of stuff is so cool. There’s another one, Kings of the Night, which is literally Bran Mak Morn calling upon the power of a lost king. It’s Kull by name. Kull’s basic ghost or spirit comes forward and helps lead Bran Mak Morn’s army into battle. You’re like, “Ah.” Well, this is the original multiverse. This is the original shared pulp promise. And that’s really cool as well that we can take these little tethers and go, “You know what? This is the grandest of adventures across all these pulp milieus, and what is the potential of that going forward?” In a way that you couldn’t do with a monthly book in the seventies and that hasn’t quite been done before. And that’s the exciting part for me is looking forward and saying, “Man, there’s so many cool stories we can tell. You can drop in and enjoy any of them, but if you stick with us on the journey, you’re going to see something so much bigger and cooler to come.”

You’ve had to adhere to more stringent universe-building before. I know this isn’t your first time writing Conan, but what is it like switching from something with reasonably flexible parameters to, say, Marvel’s continuity-bound superheroes.

I had a great time writing content at Marvel. I have a great time writing superhero stuff and Dungeons & Dragons and all kinds of different properties – Rick and Morty and Stranger Things and all kinds of different stuff. But I think what’s cool about this is, there are little stakes in the ground, but it’s much looser in between. Because we don’t have the tight continuity of a superhero universe, we can forge interesting pieces. And the Hyborian Age is meant to be this mysterious and vast place, so we can put down new areas and just say, “Here is some new kind of thing.”

And it speaks to these broader pulp patterns, but we can make stuff too. And as long as it doesn’t directly contradict what’s been said, why not? That’s fun. And have fun with those kinds of elements of it. And the readers are more than happy to come along for the ride as long as it speaks to those kind of inspirations and ideas that they know the character does well. And that’s super fun for me. I love being able to build stuff out. I love being able to take these kind of ingredients and funky things that are referenced in obscure pulp stories or even poetry that Robert E. Howard put together and go, “Okay, if you read the story as just a comic reader, you’ll enjoy it. And if you are a fan of the Robert E. Howard canon…” Or in some cases, I know this sounds dramatic, but I’m not kidding, there are scholars of the material. They read everything and they notice that we’re pulling some little funky thread and they’re delighted as much as I’m delighted to have that kind of stuff to be able to pull on, that there’s enough foundational material there that I can always keep digging almost archeologically. But on the other hand, it’s not telling me, “You must use it like this.” It is absolute in its rules or in its prior established usage.

Absolutely. There are varying degrees of appreciation here.

Right. And everything from someone who only knows Conan from the Arnold Schwarzenegger movie, all the way to… Everyone knows the name. It carries certain pop culture cachet, but a lot of people aren’t well-read in the material. And if they’re read, they’ve read a weird mixture of the comics and the pulp stories and some of the stuff that was rewritten and overwritten by Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter from the sixties and seventies. Very few people are carrying encyclopedic knowledge of this stuff, and that’s to our advantage where I can cherry-pick and go, “You know what? But why do you remember the movie so much? Because it has this very cool, powerful, potent storytelling.” Great. I want that feeling, even if I’m not going to use the movie specifically. If you were a fan of the movie and you pick up Bound in Black Stone, that feels like your Conan. But it’s not Arnold. It is that adventurous character.

CONAN THE BARBARIAN: BOUND IN BLACK STONE is out now from Titan Comics.