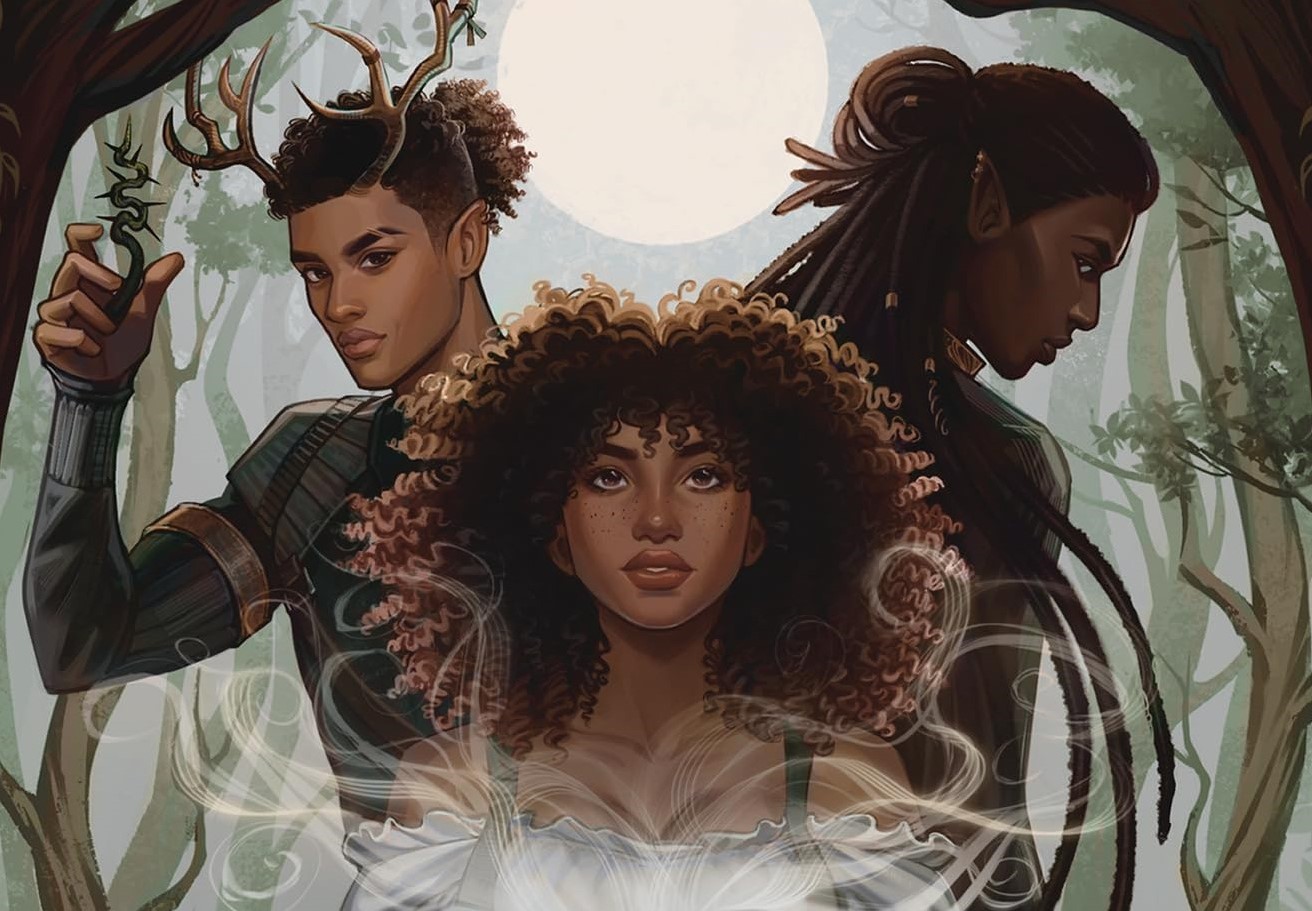

Analeigh Sbrana’s Lore of the Wilds is a twisty, cosy female-fronted fantasy romance with a deliciously rich setting and impressively thorough worldbuilding. These sprawling fantasy landscapes are inhabited by all manner of quintessential fantasy creatures and tightly created characters – Sbrana has created an expansive, immersive world in which to play out the deftly tied strands of her plot and the subtle real-world social commentary that runs through it all. The first part of a duology, the novel expertly weaves a plot rich and complex enough that, by the end, the stakes and setup of the second are already high and dense.

Lore of the Wilds opens in the fantastical Duskmere; at a glance an idyllic woodland setting, yet reveals itself early on to be essentially a prison for the humans of the novel, who are held without any magic or understanding of the world by the controlling and all-powerful fae race. Sbrana alludes to these deep political undertones through her main character, the titular Lore. Lore is a young black woman, well aware of her own mind and worth, who runs a cosy apothecary and helps the running of Duskmere’s orphanage while fighting to change the psyches of those around her with her understanding that Duskmere is sheltered, unreal, and there is more to life than that which the fae have allowed the humans to experience.

Blending the quintessential fantasy tropes of secretive political tensions, ties to family and honour and a sense of duty, Sbrana’s novel opens with its stakes very clear and its protagonist determined. As catastrophes begin to plague Duskmere and Lore is pulled away to work in the castles of the fae, these early-start plot strands begin to slink around each other in a manner pleasantly intriguing. Black female protagonists are typically underrepresented in the fantasy genre, so straight away Sbrana’s novel feels fresher, more powerful for giving an unwavering voice to those who the tropes of fantasy often don’t forefront while comedically drawing attention to the subtle differences and difficulties that Black characters would face in fantasy settings. It is a subtle suggestion, a quiet attention to detail that opens an entirely new dimension of fantasy.

The magical element of Lore of the Wilds comes into play while Lore is cataloguing the fae library; not quite understanding the nature of it or why fae have it and humans don’t, she is tasked with finding the magical tomes and bring them back to the castle authority. The grand, sweeping setting of the library with its stained-glass windows through which Lore watches the seasons slowly pass and dusty misalignment that she progressively cleans and fixes makes the vastness of the castle and her task seem human and small enough to deal with. Sbrana humanises the political tensions, the lack of understanding, and the shimmer of magic through her deliciously three-dimensional protagonist. Lore searches for magic for the fae, while nurturing a realistic and rebellious drive to find answers and power for herself in order to set her people free. Tied to those she has left behind in Duskmere and faced with the promise of understanding, Lore becomes at one with the setting and drive of the novel, often alone for great stretches, and as a protagonist becomes deeply comfortable and enjoyably relatable, with a subtle suggestion of feminism driving Sbrana’s construction of her.

Lore is aware that, as a woman, she faces additional difficulties, even more so as a Black human, and yet, does not particularly seem to let it affect her or her work. It is an interesting suggestion that female protagonists don’t change the fundamental concepts and tropes of fantasy novels, rather just offer a fresh lens to view them through. There is an enjoyably innate femininity to Sbrana’s style as well. Written often in a lyrical style and given to stretches of imagination and dreams, Sbrana’s writing is richly complementary to the subject matter, and means that when strands of hidden magic start to call for Lore by name, it seems realistic and reasonable even when it is left pleasantly intriguing and inexplicable. This first phase of the novel strikes a harmony between the insurmountable and confusing, and the strength of the humanness.

Whilst living at the castle and facing human-fae racial tensions and concern for the ongoing struggles in Duskmere, Lore meets the initial romantic interest, Asher – a fae guard tasked with watching over her and ensuring her own task is completed. Asher, while not necessarily initially very friendly, adds a dimensionality to the novel that balances perfectly with the excessiveness and fear associated with Lore’s task of cataloguing the library for magic. Sbrana sets Asher and Lore up almost straight away on a quintessential ‘enemies-to-lovers’ path; while appearing to dislike each other on the basis of race and station, taut dialogue, comically clashing personalities, charming self-denial and tenuous flirting suggest immediately to a reader that this is not the case. Lore and Asher are continually drawn together almost against their will – Asher is tasked with taking her to the market, watching over her during an autumn festival, and making sure she is comfortable to work. Again, the lyricism of Sbrana’s descriptive authorship and often startling richness of her settings give a sense of high fantasy to even the mundane exchanges between the two, with descriptions of magically-infused festivities beneath the moon and bustling, sensually rich market trips giving depth to their interactions and allowing their romance to blossom in a way that feels ultimately natural despite the initial ridiculousness of them bonding. Sbrana ensures that Lore never falls into the trap of a romanced protagonist and forgets the depth of the strands holding her there – even preoccupied with Asher, Lore remains driven by her work and drive to free her people and retains an impressive three-dimensionality that ensures a reader is never alienated by her behaviour or personal reasonings.

Lore’s personal drive and suspicion of the fey is ultimately the key factor in the eventual escape that she and Asher have to make from the castle, newly armed with magic and a deeper understanding of fey villainy and the need to save her people. Sbrana’s fantasy worldbuilding is showcased as the two travel across perilous mountains, tend to their wounds around campfires in caves, and see off bandits seeking to return them and their magic to the castle. Lore develops the magic she can wield, still not understanding it, while Asher teaches her to fight. Their romance builds as they travel, heating up their tiny sleeping quarters and smouldering over campfire discussions. The magic begins to blossom as well, revealing ties to Lore’s ancestry and the cycles of the moon and stars through the night sky. Lore of the Wilds continues to have an enriching, delicate femininity informing the harsher tropes of the novel; an interesting and powerful balance and unique allure.

Lore and Asher arrive eventually, romance built to a point of possessiveness following a steamy kiss one night and the stakes higher than ever now they are fugitives, to Asher’s home town, where they take refuge in the ‘Exile Inn’, run by an old family friend. They join forces with Asher’s old friends Isla and Finndryl – a pair of fey twins who embody one of the political tensions between light fey and dark fey – Isla is a beautiful, comedic light fey, while Finndryl is brooding, unfriendly, and intimidating with his huge dark wings and ability to use magic. Finndryl is similar to the way Asher was described earlier on in the novel, suggesting that Sbrana’s prioritisation of her female characters has left the male ones slightly one-note, given to the ‘sexy bad-boy’ trope to increase the romantic intrigue, for it seems immediately that Finndryl dislikes Asher and has an interest in Lore and her stolen knowledge. In this sense, the eventual love-triangle seems inevitable.

The Exile Inn forms the setting for the next phase of the novel, where this found-family of humans and fey collectively work out a course of action for saving Duskmere from the tyranny of the fey, and to return the Exile Inn to its former glory. Again, Sbrana has humanised a sweeping, insurmountable task with a smaller, more human one and uses it to develop her characters – their interactions are amusing and charming as they drink together into the night, cook in the Inn’s kitchens, and visit the dense, sprawling markets of the town. Lore and Asher’s romantic tensions and the blossoming friendship she shares with Isla give the harsh realities of the novel a quainter, more exciting human edge, as does the improving fortunes of the Inn itself as a result of Lore’s attempts to restore it to its halcyon days. At the Inn, the plot builds on multiple levels – magically, as Finndryl teaches Lore the source of magic and how to wield it; politically, as Lore uses this magic to scry in the sweeping forests to see her people and learns that they are held captive in the castles of the fey, and romantically; Asher is away holding off bandits, and the attention of Lore switches slowly to the dimly lit evenings in the basement poring over magical documents with the previously aloof Findryll. There is a hint of the earlier enemies-to-lovers trope, with Finndryl softening slowly just as Asher did in the castle.

The pace of the book begins to lose itself somewhat here, becoming slightly swamped in the depth and complexity of its own plot. Where earlier Sbrana’s sweeping fantasy was able to develop under its own natural speed, inching across terrain and deepening between characters, it becomes almost frantic when Lore manages to plot out, break into, break back out of, and return home from the Fey Queen’s castle to rescue her old friend Grey in the space of a single chapter. The Fey Queen had up until this point not been part of the lore, and doesn’t seem to return in a meaningful way once Grey has been rescued. The suddenly rapid pace of the novel, combined with the depth and richness of Sbrana’s worldbuilding clash heavily enough to impact on the reader’s ability to suspend their disbelief in the fantasy of the novel. The Fey Queen element of the story is equally rich in magic – Grey is a human held in alchemical thrall, Lore executes a complex journey and plan to reach the castle and employs her magic to hold herself away from the Queen and rescue Grey, but the almost frenetic pace of it all occurring makes it difficult to properly immerse a reader, and to feel the full weight of these occurrences. It is almost a shame, since the rich background of the Fey Queen keeping human pets is a deeply interesting and spooky element that could have been elevated to the same sweeping high fantasy of the magical library. It seems as though Sbrana has discovered a need to have Grey in the forefront of the plot and has achieved his presence by any means possible. Once they return, it is similarly glossed over by Finndryll and even Grey himself, even though in the timescale of the novel, Lore had been gone for two weeks or more. It adds a sense of urgency and drama to the steadily tightening plot, however, and is interesting when considering the subtly feminist suggestions that Lore represents that she is the one to rescue a man from a castle, rather than the expected other way around.

Grey joining the group at the Inn coincides with Asher’s return, and elevates this cosy, tight-knit found family. Readers become fully immersed in the interpersonal tensions and friendships, in the confused romantic feelings of Lore, and, in the forefront, the now imminent attempt to save the humans of Duskmere from the fey. The plot and occurrences of the novel has been steadily darkening as Lore comes to understand the true reaches of the fey tyranny and the possibilities of a magic that she doesn’t understand – war is building in Lore of the Wilds, but so is the humanity that has propelled this mismatched group into it in the first place. Powerful ideas of freedom and duty swirl around stolen moments of steamy romance and soul-searching questions of origin and purpose.

The culmination of the novel comes with the attempt to break the humans out of the fey castle, and is again in the twisting quintessential fantasy style, all brought together by the greater good. Sbrana leans into the darkness she has been cultivating when the group find a number of human women captive in the fey dungeons, used for fertility research and theories in what is a surprisingly sinister, almost dystopian turn to a novel so imbibed with magic. It is an ingenious and unexpected twist, and as the machinations of the plot come to fruition it is clear that Sbrana has engineered everything to point in the directions that they discover by the end. The women are held by the true villain of the novel, a plot twist that is almost entirely impossible to see coming and perfectly fantastical in its set-up without seeming contrived or unbelievable. Darkly lyrical prose and threatening dialogue twist around sweeping realisations and plot implications as the true malevolence is revealed and blossoms into its full form. The unveiling of a core, seemingly unstoppable villain in all its dark glory from the deepest, most rupturing twist of plot is a stunning end to the novel, a gut-punch of panicked questions and bitter understanding.

The ending of Lore of the Wilds is the ultimate cliffhanger, and a perfect set-up for Sbrana’s planned sequel. By the end, it is clear how every element of the novel has been half of a whole – be it the romantic tussling between Finndryl and Asher, the core and source of magic itself, or the intentionally incomplete knowledge that Lore has of her own people and background. Sbrana has given her audience just enough to understand the immediate, and with the second appears to promise an understanding of the sweeping branches of knowledge and machinery that has been driving it. Lore of the Wilds ends with shattering implications, and reels under the weight of its own twists. Rich, real characters and their deep bonds with each other bridge the chasms that darkness and evil have broken into the fabric of Sbrana’s fantasy world. Lore, despite her difficulties, remains as strong as she was at the beginning, and the found family of friends and lovers remains as tight and determined as they were at their formation.

Ultimately successful despite some very minor issues with pacing and timekeeping, Sbrana’s novel is a cosy entrance to a world that mutates and evolves into a thickness of evil that means a reader, by the time they leave, are just as weathered and worldly as her characters have become. The richly built and established world stands as a reminder that the events of Lore of the Wilds are not over, they are merely – as they have been throughout the entire novel, subtly and quietly – just brewing to fruition.

LORE OF THE WILDS is out now from Harper Collins

Click cover to order from Amazon.co.uk