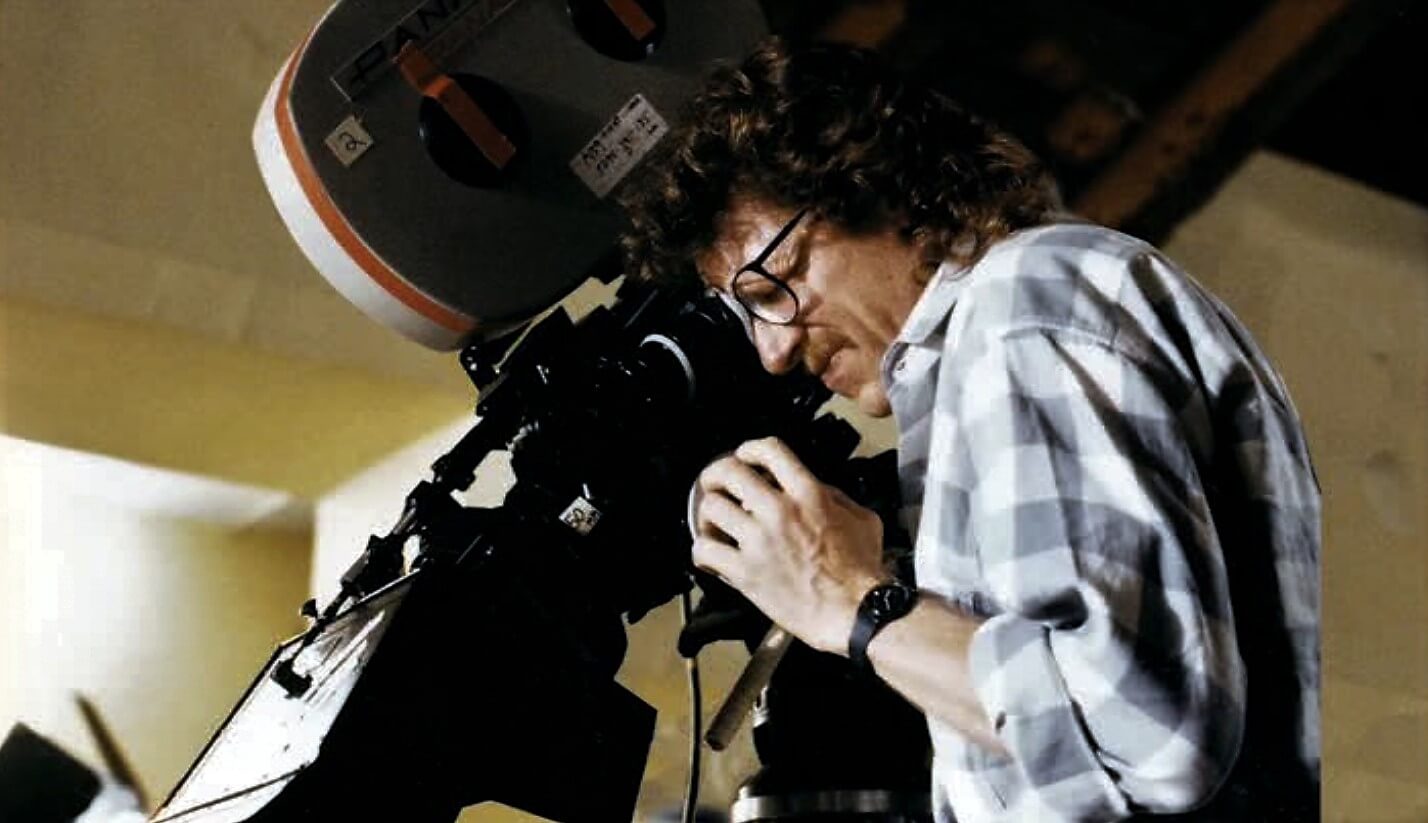

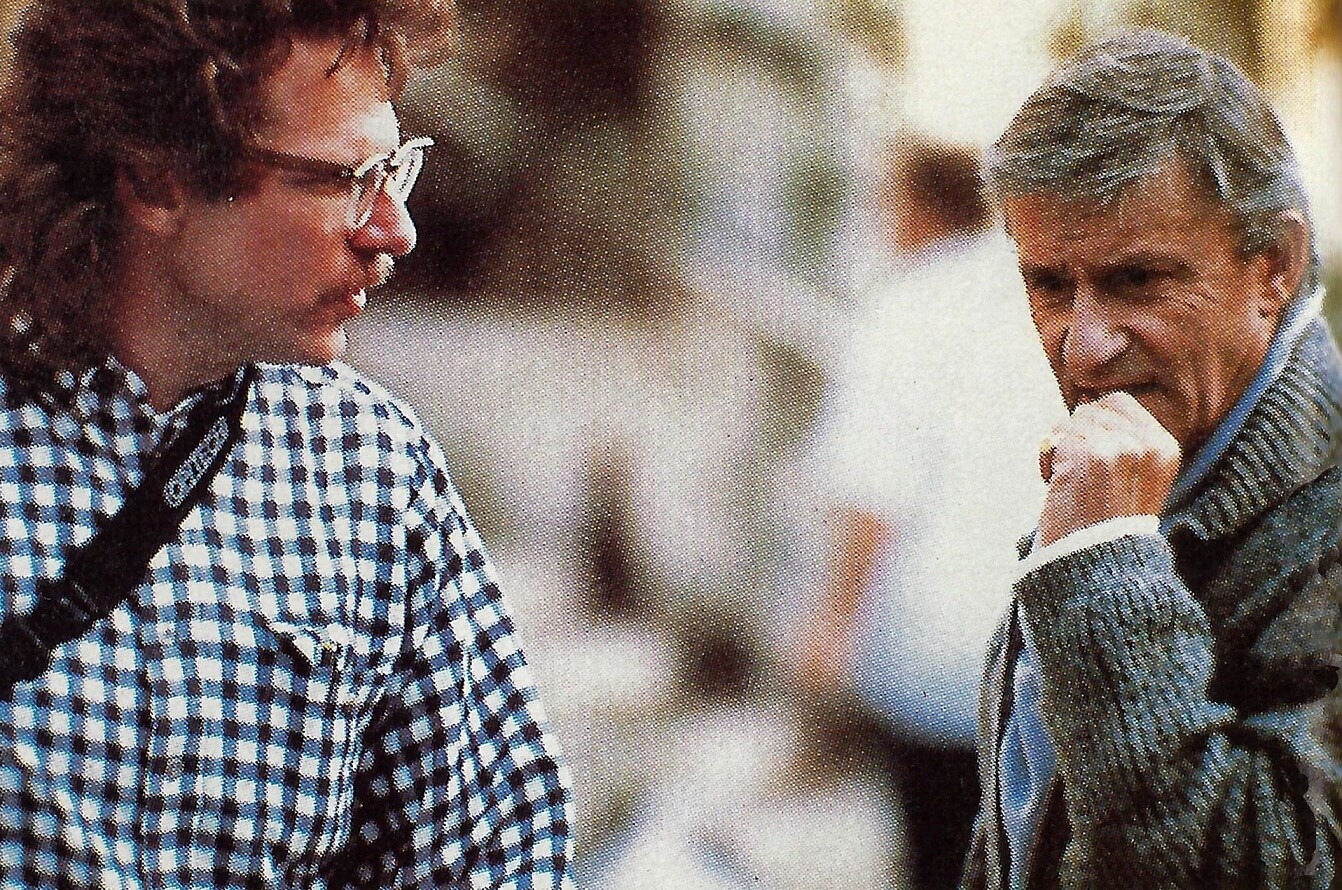

Tommy Lee Wallace is a huge favourite of many a genre fan. Having worked with childhood friend John Carpenter on Assault on Precinct 13, Halloween, and The Fog, Tommy famously made his feature film directing debut with 1982’s Halloween III: Season of the Witch. In addition to that picture, he also directed beloved efforts such as The Twilight Zone, Max Headroom, Fright Night Part 2, and the 1990 It miniseries. With the Halloween franchise now stalking back to the big screen, we caught up with Tommy to discuss this iconic series, why he turned down Halloween II, the initial negative reaction to (and redemption of!) Halloween III, and a whole host more.

STARBURST: When was it that you and John Carpenter first became friends?

Tommy Lee Wallace: John and I grew up in the same town – Bowling Green, Kentucky – and we knew of each other since childhood, became close friends as teenagers around music, our own attempts at singing and playing guitars, and certainly our appreciation of rock ‘n’ roll, particularly the British invasion – The Beatles at the top of the list. When John went west, I went north to Ohio. I went to Art School, John went to Cinema School. We remained in contact, and I went to visited him at a very critical point. I liked what I saw, so when I graduated I went west as well, and we continued our friendship.

When did you first realise there was the potential of a career in filmmaking for you?

Obviously, USC is a feeder school for the movie industry, so I couldn’t help but notice that. The people who had gone before – perhaps most vividly George Lucas – were making their way as filmmakers. It hadn’t really occurred to me until I was in film school that that might be a career path. John was deeply, highly motivated since he was a youngster. He knew exactly what a film director was and what a film director did. He had towering ambition in that direction from an early age. I was learning more all the time about that, as I took some cinema courses at Ohio University. I was getting a great grounding in the arts, the visual arts – graphic design, specifically – so I was bringing a little different perspective. It didn’t go unnoticed that everyone was referring to cinema as the art form of the century. I was seeing the creative possibilities, at first of animated film – which is what landed me at USC – but very quickly after that live filmmaking really captured my attention and I fell in love with it.

You famously turned down the chance to direct Halloween II, instead deciding to make your feature film directing debut with Halloween III: Season of the Witch. What prompted you to make that decision?

Well, I had established myself – in my own mind, at least – as a director long before that, at University of Southern California. Sequel thinking and sequel-it is, and the good and bad that went with that, hadn’t really hit yet, so immediately following Halloween came The Fog. I was really, really getting rounded as a filmmaker in general thanks to my editing experience on Assault on Precinct 13, Halloween, and The Fog, and so I was ready. It was obvious to everybody I was ready, and John and Debra [Hill] knew that I was ready. It was kind of natural for me to inherit the director’s chair for Halloween II. Unfortunately, when John and Debra turned the script in, I just hated it; I thought it was the anti-Halloween, it was everything Halloween was not. Halloween was about suggestion and shadows and ideas, whereas Halloween II was a lot more about guts and gore. I just didn’t like it, and I selfishly thought this would be a terrible way to try and start a film career – on a movie that you don’t like or respect. Moreover, it would’ve been a disservice to John and Debra to give them a director whose heart wasn’t in it. I knew I was passing up a marvellous career-starting opportunity, but it just wasn’t the right thing to do – so I said no. I was delighted when they returned to me again on Halloween III, because that was an open ticket, that was an altogether different idea that had no script at that point. [Quatermass’] Nigel Kneale was preparing a script, but I knew it would be very, very different. Knowing Nigel’s reputation, I knew it would be well written, so I jumped at that chance.

When you got offered Halloween II, how similar was it to what we ended up seeing on screen in the final film?

Exactly is too strong a word, but it was pretty much that script they went with. John’s idea was a five-minute-later kind of sequel. I had been advocating an idea that was more a five-years-later kind of sequel that actually came to fruition more-or-less if you saw H20 – the one Jamie Lee Curtis returned for. I thought that was good stuff, it was really interesting to come to a person who’d be traumatised that way years later. I can’t fault John and Debra’s choice on Halloween II because it went out there and made a tremendous amount of money. It was a success, there was an audience for it. There was a kind of an arms race that had happened in the meantime. After Halloween came out, it had several imitators – including Friday the 13th – and there was an escalation in each one as to the size of the bad guy, the size of the knife or the axe or the chainsaw or whatever weapon of choice, and the amount of blood and guts and gore. I think John had his ear close to the ground on that and was very sensitive to the fact that if Halloween II wanted to make an impression then it would have to keep up with those other guys.

To this day, Halloween II has one of the most brutal deaths in the entire franchise, when Michael scolds off the face of Pamela Susan Shoop’s character.

It was a result of that arms race I was referring to. I did movies with some pretty grizzly things happening in them, but somehow Halloween – the making of Halloween, the way it was done – it meant a lot to me, as I’m sure it did to John and Debra as well, and that film is really a classic, as it’s proven to be, and it had the kind of style to it that did not involve pandering to guts and gore. Coming on the heels of Halloween, it just rubbed me completely the wrong way. So I just held my breath and said no.

You said Halloween III: Season of the Witch was essentially a blank slate, a blank canvas. The story we actually got to see, how much influence did you have on that?

No, that was built on a script by Nigel Kneale, a writer John had admired for all of his career, notably for his work on Quatermass. It was a really interesting script, really original. I’d say 60% of what Nigel wrote is still there. Unfortunately, in my view, he took his name off of it because he felt that we’d fooled around too much, desecrated it in some way – so he didn’t want to have his name on it. John had rewritten Nigel, John did not take any credit for it. I rewrote John, and I was the man left with the credit. It’s not an accurate credit, but that’s the way these things go. I certainly wrote a lot of the movie, but I’d still say Nigel’s work was 60% of what you see.

You and John were very keen to take the franchise in an anthology direction – a different film, a different setting each Halloween – whereas Moustapha Akkad was more about Michael Myers. Was there any time during your early involvement on Season of the Witch where there was talk of Michael being a part of the movie, or was Michael always out?

No, John and Debra were sick of Michael Myers and the Halloween legend as of Halloween III. The only reason they did it was because the agreement was it would not involve the old icons, which at that point weren’t exactly icons yet. As I said, sequel-itis hadn’t struck everyone yet. When we first heard the news, we were kind of like, “Why would we do a sequel? That was a perfect movie! What else is there to say?!” And yet, they understood that that train was leaving the station whether they were on it or not. So they agreed to do it. In hindsight, Halloween III should never have been called Halloween III. It should’ve simply been called Season of the Witch. But then, you see, it never would’ve gotten made. So it was a kind of a pact with the devil. What could’ve saved the day is if the powers-that-be – including ourselves – had had the will and the foresight and the drive to advertise it properly. To let the audience know what we had in mind, which was, as you say, an ongoing series of movies on the subject of Halloween, one per year, any of which could’ve spawned their own set of sequels. I still think it’s a great idea. There must be a thousand stories you can tell, but I don’t think Universal even got it or liked the movie. So it didn’t get any sort of support. It also developed a terrible backlash of people going into the theatre rightfully expecting The Shape and the knife and Jamie Lee [Curtis], and getting instead this whole new story. It has taken all this time to develop its own audience. It has a ferocious following of loyal people who love the movie, but many of them had to get over the fact they felt shanghaied. And at the beginning, sure, it wasn’t what it was advertised to be. That was just a fundamental error, just a mistake. But it could have been remedied simply by good advertising that set the table properly, and that just didn’t happen.

How tough was it to receive such a negative response to your feature debut?

It was crushing. I wasn’t ready for the rejection and the negativity around it. Although, as I say, I think all of us were naïve. We should’ve been able to see that coming. However, redemption is sweet, and after all these years it’s all better. I go to these festivals where they celebrate horror movies and fans come and like to chat, and it’s overwhelming – the t-shirts, the hats, the support. All the fans just love it! And they all sort of have a chip on their shoulder about it, and I say, “You can relax now. Anybody who puts it down at this point in time, all you have to do is look ‘em in the eye and say, ‘Did you not get the memo? This is a good movie. Sorry about the title.’”

You talked about Halloween II being quite gory, but Halloween III certainly has its intense moments.

I can’t preach too much about the gore of Halloween II because I, you know, pull the guy’s head off and all this grizzly stuff. To me it was different because it wasn’t Halloween. For me, Halloween was a sacred territory that shouldn’t be messed with. John and Debra had every right do everything they wanted to, and they did and it made money – end of story – but I didn’t respect it.

Was there anything you wanted to do in Season of the Witch that was flat-out shot down?

Oh, no. Let me give a real tribute here to John and Debra. They were a director’s dream in terms of support. For a first-time director, the freedom I had was unheard of. Right down to the final cut, John respected my opinion to the degree that it was as if I had final cut on the movie. He was that permissive and lenient and trusting of my own vision. The best example I can give you is, after we had the movie put together – it was all ready to go – I got a call from John and he said the people upstairs had a problem with the ending. They wanted us to change the ending somehow and make it softer, give the world a little hope that this problem had been solved or mitigated. He said, “I’ll do whatever you want. If you want to keep it the same, keep it the same. If you want to change it, I’m with you.” Now that’s serious creative support. My hat is off to John forever and my gratitude endures. By the way, that ending was more than just the ending I wanted for Halloween III – it was the ending that Don Siegel wanted for Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but the studio made him tack on the sort of little extra ending in the police station when we learn help is on the way, it’s going to be alright. Bullshit! I hated that. I hated it on Don Siegel’s behalf. So, in my own modest way, I felt as though I was setting things right by giving Halloween III its proper ending.

With Michael or without Michael, there never tends to be a happy ending to a Halloween movie. It’s either doom ‘n’ gloom or ambiguous at best.

After the first one, for sure – which was almost accidental. The shot of Donald Pleasance looking back down at the ground and The Shape is gone, that was an afterthought. That was an editing room decision. It was, “Okay, there’s the guy dead. The end.” Just by adding a bit of bare ground after Nick Castle walked out of the frame – I shot that shot by the way, unofficial second unit while John was shooting more important stuff across the street – whimsically I got Nick to walk out of the frame so we had an empty frame if we wanted it. All of this, The Shape living on, it’s somewhat an afterthought. He’s everywhere. And by the way, all those empty streets at the end were also afterthoughts. None of those were planned shots; they were shots that we gleamed in the editing room before slates, before actors walked into frame to do the scene. They were stolen shots that we just conjured up in the cutting room to provide that extra oomph of empty streets, fear, to generate this legend. Totally an afterthought.

And Donald Pleasance conveys that fear so well. If he’s scared, then we all should be.

Yeah, it doubles up on it and helps provide momentum. Remember, the saying is a film gets made three times; when you write it, when you shoot it, and when you edit it. And we certainly added a layer in the cutting room.

Was there every any talk – with or without Michael – of you coming back for Halloween 4?

No. I think that in Hollywood, if you have a failure then the phone does not ring. You really have to dig your way out of a hole like that. It was tough there for a while afterwards. There was no talk of another Halloween movie involving me, and not to sound like sour grapes or anything, but I wouldn’t have gone near it. You get pigeonholed so quickly in the movie business that what you want to do next, if you can, is a comedy or a mystery or a western or something – just to keep from getting hounded down into a pigeonhole. You really have to be strong and you also have to say no, if you can, to some opportunities that could pay your bills in order to wait for maybe a role or a job that expands your horizons and takes you out of the pigeonhole. That’s very difficult if you’re in it to make a living and try and pay your bills while raising a family or whatever. I found it terribly difficult. The phone would ring for me, but it would ring mostly for horror. How many times would I have to say no before something else would come along? Well, you know, after a while you say yes simply because maybe you like the project, but you’ve also got to pay some bills.

You mentioned how Halloween III really knocked your confidence. When do you feel you really got that confidence and belief back?

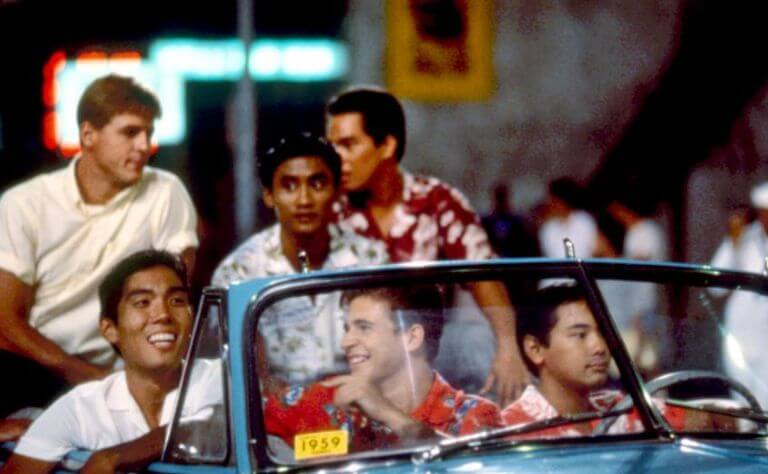

I was back on the horse immediately looking for work, but it was quite a bit of a struggle there for a while. I got a call from a guy who wanted to make a coming-of-age movie in Hawaii – that was in 1984 – and boy, rock ‘n’ roll? 1959? It was like somebody handed me a ticket to paradise, it was just great. I’d say by then I was back on the horse fully. That movie became Aloha Summer, which is still out there. Not quite a great movie, but a pretty fun and interesting picture about a culture clash in Hawaii in 1959.

On the anthology topic, you also got to work on some episodes of The Twilight Zone. How much fun was that?

It was terrific. At the time I was leaving television. It wasn’t the way it is now, where I think television is to some degree where the real goods are. It’s just golden and wonderful with so many fantastic shows, especially longer-form series. At that time, you had to be careful not to get categorised. TV sounded like a cheaper thing, like a lower creative form. So I was very reluctant to take on television in the beginning – I was a real snob, honestly – but Twilight Zone, and later Max Headroom, those were amazing television opportunities that I just jumped out. I like and respected them, and they seemed to have a real resonance to the original Twilight Zone. It was clearly people who knew what they were doing and who had some pull to get quality talent. I jumped at the chance. It was a ball, it was so fun to work on, it was a pleasure.

While TV is booming these days, do you think that the concept of anthology television has been lost a little bit over the past few decades?

It seems to me that the models have been turned inside out. You can do a true anthology, where it’s a different story every week or even two or three different stories in one week, or you can do a running series that at the other end of the spectrum attention pays. If you miss the first one you might as well not watch. Then there are in-between permutations, where it’s a running series where there’s a new story every week or the A story changes every week but the B and C stories continue. It’s thrilling for me, and I think it’s a fertile field.

Yeah, they really had the right people at the right time, and they did something original and fascinating, really hypnotic at times. In television, unlike motion pictures, the hierarchy is divided up. In stage plays, the playwright is king. In feature films, for the most part, the director is still king. In television, the writer tends to become the producer, and the producer is most certainly the king. So all of a sudden in television, you get all these productions where the writing is splendid, it’s tremendously good, and yet it doesn’t get screwed up or confused or reedited beyond comprehension, because that writer is producing their own show. That’s a good way to have it, creatively speaking. I think most people have figured out that movies that get made by committee are generally not very good. You need someone in charge whose vision is worthy of respect. If you’ve got the wrong visionary, you’re not likely to be very good. If you’ve got the right visionary and they don’t get interfered with too much by too many people or too many executives who think they know what they’re doing, you can have a good product.

Following The Twilight Zone, Max Headroom, and Aloha Summer, you’d go on to direct Fright Night Part 2 in 1988. After your experiences on Halloween III, was there any trepidation about tackling another existing property?

By then, I did feel I knew a thing or two about how you make a horror movie. It was the situation that led me to step in to it. It was with friends for a small company, and it was clear that if I jumped in to this I would have a lot of control and a lot of support. These folks knew what they were doing around film directors. By this point, I’d had some brushes with television that weren’t so much fun because you had people who treated the directors as like an island, just somebody to direct traffic. I didn’t enjoy that at all. And here was a feature experience. A sequel, if you’ve got good support, can turn out to be a good movie. I’m proud to say Fright Night Part 2 turned out to be a good movie.

Fright Night itself is one of the many horror movies to get the remake treatment in recent years. Are you a fan of remakes in general, or do you have to take each film on its own merit?

I think you have to take them one at a time. The phenomenon of remakes is understandable from a business point of view. The film business doesn’t like to take risks, but what business does? If you have a successful risk taker, that’s great. But then there are three or four next to them who’ve taken a risk and crashed and burned. I get it, but it still mystifies me when people remake movies that were good the first time. It just seems that the odds are that you couldn’t possibly match the first one. That seems to be what happens. Fresh faces, fresh eyes are being born every day, so the original, in a way, doesn’t matter if enough time has gone by. It’s a whole new audience getting something meaningful out of this whole new experience. Having said that, I do think that it’s gotten ridiculous to the point that Hollywood is devouring its own tail, consuming itself. There are so many worthy, interesting movies that go abegging because nobody will finance them, whereas they’ll jump at the chance to finance the next comic book movie or the next sequel or prequel or remake. It’s really got ridiculous. It just creates a wasteland for new material. That new material is the lifeblood for any business, for any genre. It’s incalculable the loss of talent from Hollywood. There aren’t enough film projects being picked up, writers have quit writing original material because nobody will buy it. You can’t just get that back. It’s very short-sighted. I think we have a dearth of visionaries in the movie industry. And where the new visionaries are going to come from, it’s clearly not the Hollywood establishment. Like I said, they’re consuming themselves. It’s not just about the film business, it’s about our culture at large. I think the hope of the movie business is in the independents. The fact that you really can take your cell phone and a couple of lights in the trunk of your car and make an interesting picture without all of the dead weight that a studio simply has to carry with it in this new century, I think the independents is where it’s at for the future.

In 1990, you famously helmed the It miniseries that is so beloved by so many genre fans, which UK fans were treated to over the space of two Saturday evenings.

My experience at these festivals is people will walk up to my table and say, “Oh, you just scared the pants off of me when I saw your movie.” That’s usually Halloween III or It. I’ll ask them how old they were when they saw it. Usually it’s, “Err, about six…” and their parents weren’t aware that they’d watched it.

Were there ever any plans to have It be more than just a two-part tale?

I came in to this project rather late. I don’t know how many hours of television they were planning, but it was much, much more than two nights. It all got whittled down and an awful lot of the original budget had been taking by at least one set of producers who didn’t stick around for the movie. They were replaced by another set of producers, Green/Epstein, friends of mine, and they proved to be really supportive on the picture. But yeah, a lot of the budget had gone by them. We were working on my usual low budget scale. We had to pull it out of the air with cardboard, chewing gum, and tape.

Had you read Stephen King’s novel before you were involved with the feature?

Before I got the call, I had not read It. Of course, when I got the job I immediately sat down and read it. I was a Stephen King fan but not a massive one. I had read Firestarter and Carrie and enjoyed them. But just the script, it was evident this was going to be extremely special. It was extremely well written by Larry Cohen, so I jumped at the chance.

Was there anything from the novel that you wanted to include but couldn’t?

I wanted more out the second night. It seemed that Larry, and presumably Stephen, had decided to not even try for the comprehensive, colossal climax of the novel, which involved metaphysical reality and a battle in inner space. It was kind of bigger in scope than you could ever hope for, certainly on our little budget and schedule. However, they abbreviated it so early I felt readers of the novel would feel short-changed without a little bit more. Larry Cohen’s night one was just a brilliant piece of writing, with a lovely coincidence that a night of commercial television involves seven ads. You were going to have seven different chunks of storytelling interspersed with commercials. The fact that Larry very deftly turned those seven acts in to seven character points – there’s seven main protagonist characters in the book – and that really, really made it sail. My hat’s off to Larry for how he crafted that. I would’ve loved to add a bit more, to somehow tackle the good vs. evil cosmic battle. That was beyond me. What I did not care for in the book and made no attempt to include in the movie was the idea that six of the seven were boys and Beverly the only girl, and in the book they all have sex with her. I thought that was trashy, I didn’t like it at all. It didn’t click for me. I thought it was especially tasteless because the entire subtext of that book is about child molesting, it’s about unprotected kids being vulnerable to somebody taking advantage of them. It’s just sitting there under the surface. I completely accept that and think that’s a worthy subject, but then I thought Stephen King undermined it by what can only be described to me as an adolescent fantasy on his part – that all the boys have the girl. That’s a strange idea of bonding.

And was it yourself who brought Tim Curry in as Pennywise?

I can’t claim credit. Jim Green and Mark Bacino, my producers, had the most to do with that. Most of the casting for It’s adult parts were telephone casting. We didn’t need to audition Harry Anderson or John Ritter or Richard Thomas for their parts. It was clear that if they said yes then they’d be an asset to the show and do the part really well. I think Tim’s name came up, and I don’t think anybody said, “Oh, that’s a bad idea.” I think everyone was thrilled. It was a couple of phone calls to an agent, and he was on board.

Online rumour suggests Roddy McDowall and Malcolm McDowall as being other names in the frame to play Pennywise. Is there any truth in those stories?

Either of those names would’ve brought something special to the role, but I don’t really recall anyone else being considered once Tim’s name came up. That was an obvious yes.

To bring things back full circle then, what do you think makes the Halloween franchise so special to so many people?

Well, John Carpenter has always insisted on simplicity; keeping things simple. He tells a simple story, and he tells it well, and it’s a really basic story. It’s not so much about Halloween as it is about fear and isolation and a helpless situation – in this case the original title of the piece was The Babysitter Murders. It’s a simple story, that’s one thing. Another thing is one of John’s favourite notions is the idea of someone, like the bad seed, who isn’t just “If you only understood this person, you’d see blah blah blah.” He doesn’t believe in that at all. He believes that it’s possible to encounter pure evil. And that’s a pretty compelling concept, considering religions are founded on it. You put a D in front of evil and you have devil, which is religion. It’s pretty fundamental and goes pretty deep. I’ll also put an Asterix in for my own creation, the look of The Shape. When we tried that mask out, none of us were ready for the power of it. Before you even come to a story or a situation, just take a picture of that look and it’s innately, deeply, tribally terrifying – and I don’t know why to this day. It has played a big, big part and I only wish I had a penny for every image of that mask.

While it is a mask of a face – Captain Kirk – it’s so emotionless and so simplistic. Then there’s the performances over the years, the movement…

I want to put in a plug for my buddy Nick Castle. Nick is the son of a famous dance choreographer, and although Nick wasn’t a particularly vivid dancer, he certainly knew how to move and to move slowly. In subsequent films, the trend seemed to be to hire bigger and bigger stuntmen for the role, but Nick and I are both about the same size and we both knew about moving in kind of a grooved way that’s very deliberate; that’s not in itself threatening, it’s just there, it moves, it slopes. And he really, really was a tremendous asset to creating that character.

At the moment, you’ve got Helliversity in pre-production. Where are things up to with that right now?

Helliversity has been retitled The Gate, although we’ll probably retitle it again because The Gate is already an established movie that was in theatres ages ago. We’re hoping for a title with a little less grindhouse. Helliversity says what the movie’s about, but it’s also pretty grindhouse. The financing has been set up twice now, and we’re experiencing what all independent filmmakers go through – “Oh, the deal fell through” is a much bandied about phrase. I’d also ask fans to watch for Scaryland, a feature film, and a TV series which is called Midnight Motel.

Be sure to keep up to date with all of Tommy’s upcoming projects by heading over to his Facebook page.