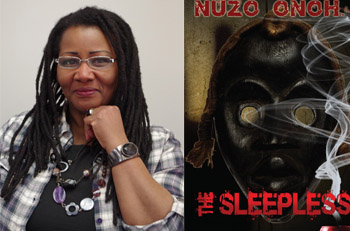

The old adage says that truth is stranger than fiction, but where Nuzo Onoh’s latest novel The Sleepless is concerned, truth and fiction often bear terrifying similarities to one another.

The old adage says that truth is stranger than fiction, but where Nuzo Onoh’s latest novel The Sleepless is concerned, truth and fiction often bear terrifying similarities to one another.

Nuzo was born in Enugu, in the Eastern part of Nigeria. Enugu was, for a very brief period, the capital of the Republic of Biafra, a secessionist state that was horrifically ripped apart by war during 1967 – 1970. Nuzo was only a small child during the Biafran War, just like Obele – the main character in The Sleepless – and, like Obele, she encountered violent death and tribal superstition on a daily basis. But the parallels between Nuzo and Obele don’t stop there, as we were to discover during our conversation.

Now living in the UK, Nuzo holds a Law degree and an MA in Creative Writing from Warwick University. She also runs her own independent publishing house, Canaan-Star, and occasionally writes under the pseudonym Alex Stranger-Onoh. But it is writing horror fiction under her own name that Nuzo is most passionate about. African horror is an exciting new genre steeped in malevolent spirits, restless ghosts and dark witchcraft, and Nuzo has already been described as its queen. On the basis of The Sleepless and her previous novels The Reluctant Dead and Unhallowed Graves, that title is very well earned indeed.

STARBURST: When did you start writing, and has horror always been your genre of choice?

Nuzo Onoh: I started writing at a young age. When I was at school, I got together with a group of friends and we decided to be a club of writers but I didn’t really take it seriously. All I ever wanted to be was a musician. I played the piano and the guitar and fancied myself as a really famous pop star. But in the family I come from, you didn’t do such things – my dad was a solicitor and they wanted everyone to be lawyers, so I went to Warwick and did exactly that to please him. I knew the Law wasn’t my calling. When my dad died, there was a sense of freedom that finally I could do what I wanted to do and so, at almost fifty years old, I went back to Warwick University to do a Masters in Creative Writing. That’s where everything started. I wrote this little piece and I read it in the class and the reaction was absolutely amazing, like nothing I ever experienced. That was the breakthrough; when I realised that I could write about things from my own culture and people would still understand it. And I love everything to do with ghosts – Stephen King is my all-time hero! – so I just went down that route.

Do you think if you hadn’t studied Law, if you’d begun writing seriously all those years ago, that you’d have the kind of voice you do now? Or is this the right time for you, when everything has just naturally come together?

This is definitely the right time! At an earlier point, I wouldn’t have been able to sit down and write with the same degree of passion and knowledge. Not only that, but when I was younger, I had no idea what genre I wanted to write in. I wouldn’t have realised that African horror is a brand that is just as exciting and relevant as horror from other parts of the world – Scandinavian horror, Japanese horror, Korean horror. I wouldn’t have marketed myself in this way or realised there was an audience for my stories.

You know, as you get older a funny thing happens. You look back on the stories you wrote when you were younger, that you thought at that time were masterpieces, and you read them now and you think ‘No way!’ When you’re older, I believe you have a clearer direction, a more focused idea of what you want to write about and how you want to write it, and you have a more mature voice. And as long as that story is inside you, it won’t let you rest until you tell it. Storytelling is timeless, it doesn’t matter how old or how young you are. So I tell everyone who’s older, who wants to be a writer, just to go for it – if you’ve got that story don’t let it stay inside. Bring it out!

There’s a wonderful dedication at the front of The Sleepless, a remembrance of the victims of the Biafran War and a thank you to the various outsiders – people like the author Frederick Forsyth – who made the world aware of what was happening.

Including that dedication in the book was important to me. A little while ago I spoke to an American reviewer who said ‘We never knew anything about the Biafran War until we read your book’ and I tell them, ‘Yes, it’s one of those wars that sits on the consciences of several governments in the world today. People don’t want to acknowledge it.’

When you recognise that one million Biafran children died – it was a genocide, it was something that the American President at the time called a genocide, and yet nobody wanted to do anything about it because a lot of governments had their hands covered in blood. When a hundred thousand or two hundred and fifty thousand lives are lost in any other war everybody screams but no-one would touch Biafra because it is so sensitive, it is wrapped up so tightly with Nigeria and the oil, the fuel crisis, and it’s a time bomb. And now the Biafrans are agitating again, they want their own country, they want to leave Nigeria because we’re not a part of Nigeria, and it’s sad that so many people have sacrificed so much and yet they’re all forgotten. Nobody remembers them.

It’s true, and at the time, Frederick Forsyth was definitely instrumental in bringing the plight of Biafra home to the British media…

Frederick Forsyth was amazing! Without him, nobody would have known about what was happening in Biafra. He went in there and when his bosses told him to come out he refused, he resigned, and he stayed in Biafra to cover the story. He persisted and persisted until the story spread to the world. Without him, nobody would ever have heard of the Biafran War and that dedication is all I can do to express my gratitude. I have nothing else I could say or give.

So are all your books tied into your experiences of Biafra?

No, only The Sleepless. For me, The Sleepless was like a personal exorcism. It’s something that’s been in my head for ever and ever. Whatever I’m writing, I always find Biafra hovering like a ghost at the edge of the page, so I finally said to myself that I had to tackle it, I had to go down that route because I experienced the war through the eyes of a child and I had to get everything that was inside me out of my system. But I knew, when I eventually sat down to write about it, that it would take the form of a ghost story. That’s what all my books are about, ghosts and hauntings.

And that underpinning of reality definitely makes The Sleepless more powerful. In many ways, the terrible realities of what happens to Obele in her ‘real’ life equal the horrors that are confronting her supernaturally.

Exactly. Because war is a harrowing thing, and people don’t realise that children who live in the war also understand the war. As a child you see so much that the adults don’t see because the dads are all gone, all the men are gone, and you’re left with mothers and old people who are busy panicking and struggling and, as a child, you’re just left to your own devices. I remember there was literally no supervision; as children, we just wandered around and in our minds we made up our own new realities. You stumble across a dead body in the road and you make up stories about it. It’s hard to explain.

In many ways Obele’s story is your story as well?

A lot of the things she experiences, I also experienced during the war so I could write about things I have seen through Obele’s eyes. Every child in Biafra would have witnessed a tremendous amount of horror, and the terrors of the war were compounded because a lot of Biafrans are Christians, practically all of them are Roman Catholics, and there’s the Catholic belief in Satan and exorcism which Pentecostal charlatans still manipulate for their own ends. But because of the war and the fear, belief in God and demons and religion was prevalent, so a lot of parents were constantly seeking the help of pastors and priests. My own exorcism happened after the war and I remember the number of priests we went to see – it was non-stop! – and the prayers – oh dear Lord! we had to wake up and pray from six o’clock in the morning to six o’clock in the evening; pray at twelve o’clock at night when all we wanted to do was sleep, and there was the screeching of all the Catholics, the holy water and the candles…

So that moment in the book, when Obele is taken down to the river to be exorcised, that happened to you?

Oh yes! I was taken down to the river too! It was late at night. I’d been having problems at school and my mum told my pastor, who decided that I was possessed by an evil witch so they had to take me down to the river to exorcise me. I remember my mum dropped me off at the meeting place and went home while they took me down to the river, it was a terrifying experience. It’s only now that I’m older I think that if they’d wanted to rape me or do anything to me they could have done it but at that time that was the last thing that came into my mind. All I was thinking about was ‘what if the river goddess comes out at me in the form of a python’ and then, when everything was over, I looked behind me as I was running away and I was sure that I would be gobbled up or turned into a pillar of salt like Lot’s wife in the Bible. I’ve never run as much as I ran that night. It was only when I reached the top of this steep hill that I remember thinking ‘Okay, I’m free, I’ve escaped the river goddess’…

But these experiences were common and what makes me so angry is that this is still going on today. Even in London, the Metropolitan Police have a department they call Project Violet, which monitors what they call Faith and Belief Abuse, because you have all these pastors, religious charlatans, who make their money by convincing parents their children are possessed – if the child exercises any form of independence or rebelliousness they say that child is inhabited by the devil. Before, in Africa, the parents would go to the witch doctor who would tell them about demons and evil spirits. Here, in this so-called enlightened modern world, the pastors say it’s Satan and his minions, and they charge a bomb to exorcise the child! And when the child is brought in for exorcism – I know of one child who was exorcised, they slugged him and slugged him until he died, and then they told the parents ‘We couldn’t get out the devil. He was too powerful.’ And that happens all the time, even here in England. But it’s hidden, whereas in Nigeria it’s open because parents actually believe they are doing the best thing for their children. It’s ignorance.

So in Africa – exorcisms, ritual sacrifice, innocent people stoned or burned to death because they are allegedly witches, the influence of the witch doctor… why is it still happening?

Superstition is deep rooted in African culture. As a child in Africa, you grow up surrounded by so many superstitions that you can’t be an African without believing in something or the other, whatever it is. On top of that, the level of corruption is hideous. Everyone wants their bit of ‘the national cake’ as they call it in Nigeria. So when that happens you get the pastors at these big open church rallies – everywhere in Biafra there is nothing but churches, churches, and churches – who claim that they can pray and see visions and speak in tongues and they become very rich because people believe they are so powerful and that they can speak to God. There are parts of East Africa and Nigeria where politicians will consult with the witchdoctor and will believe it when the witchdoctor tells them that if they sacrifice a child with, say, a particular pigmentation deficiency like albinism, the child’s blood is so powerful it will grant the politician riches, wealth, political victory, everything! Criminals believe that if they go to the witch doctor they will be armed with invisibility and invincibility. Women believe that if they go to the witch doctor, the witch doctor will cast a spell to destroy their rivals.

Moreover, if a child is different, if a child suffers from epilepsy, or is autistic, anything unusual, it is accused of being a witch. So if anything goes wrong around that child – if another child gets sick or the parents gets divorced – it has got to be the fault of the witch-child.

It is all about greed. Witchdoctors and pastors are the same thing, except one does it in the name of God and the other does it in the name of ancestors and the spirits. When are people going to grow out of this ignorance? Sadly, I don’t see it happening anytime soon. As long as corruption exists in Africa and a lot of the other Third World countries, as long as the pastors are there and can claim they speak to the Almighty, I don’t think it will change.

In many ways, African horror has similarities to the Japanese Kaidan tradition…

That’s right. They are both very dramatic, they both have their roots in ancient culture and a particular kind of storytelling. My stories are set in the Igbo culture, which has a preponderance of ghosts with unfinished business. In Japan, the majority of their ghosts also come back with unfinished business but although the two traditions share similar themes the Igbo beliefs, culture and customs I write about are very different.

What sets African horror apart from mainstream horror?

My particular style of African horror is a brand that I haven’t seen anywhere else. Africa is so vast and has so many small distant tribes, each tribe with its own special evil spirits and malevolent entities, and I am trying to contribute my own little experience, my own offering of the culture, belief and superstitions of the area I grew up in, within the framework of the horror medium. Writing shouldn’t solely be about telling stories, it should also tell the reader something about the culture the story is set within. Although I call my book African horror, if you looked at other stories from East Africa, South Africa, or North Africa they would be totally different. I’d like African horror to be recognised as a proper genre in its own right.

So what is it about horror that you particularly love? Where does this fierce connection you feel for the genre come from?

It’s all about the ghosts! I grew up with ghost stories. When we were kids, we’d have something called the moonlight tales, when we’d all gather around my uncle who would tell us stories about ghosts. Other storytellers at the moonlight tales would tell us different stories; nice stories about animals and that kind of thing, but I wasn’t interested. My uncle’s ghost stories were always exciting and thrilling and afterwards, I would go back and look at my grandfather’s grave – because even though I never met him, I always had a very close relationship with my dead grandfather and whenever my dad upset me, I would go and lie down on my grandfather’s gravestone and tell him how evil his son had been to me and to punish my dad for making me cry. After that, if my dad came back and said something had happened to his car or anything, it really justified ‘Yes, my grandfather has dealt with him!’ So for me, if it’s not ghosts, it’s not happening!

Your writing is occasionally very graphic and there are some descriptions that, when you read them, are so deeply unsettling they really get behind your eyes…

I don’t set out to make people uncomfortable, honestly – I’m just writing from a place of experience! But if you read other African women writers, you probably wouldn’t find my writing so graphic. Most African women writers, if they went down the horror route, would be told they are possessed. I don’t do churches anymore but if a pastor ever read anything I’ve written, I swear to you that by now I would be having another exorcism!

And, of course, reading something that puts you on edge is also a big reason why many of us read horror. But even for hardened horror fans, there’s a sacrifice at the beginning of the book it’s hard not to be affected by…

Because you’re praying the little boy doesn’t get killed. But I said to myself ‘if I don’t let him get killed, then I’m not being true to what really happens’. Child ritualistic murder is an everyday thing. When I was growing up, whenever the elections started in Nigeria my parents would stop us from going out. After school, we had to wait until the car was there to pick us up, you don’t walk home, because that’s when the politicians would kidnap children for their ritualistic murders. So there are certain periods when the kidnapping and sacrificing of children is high, and I said to myself ‘should I let the little boy survive that experience?’ and then I decided no, because that wouldn’t be true, because in the real sense he wouldn’t.

So what about the writing process? How do your ideas come to you?

Things happen. For example, one of the stories in Unhallowed Graves was based on something that happened to my mum’s friend, when her husband died. People believed she had a hand in his death so the only way she could prove her innocence was to drink the corpse water, the water they used when they washed the dead body, and after she drank the water they left her with the corpse in the forest for three nights. If, after the three nights, the corpse didn’t wake up and take its revenge, she was innocent. That always stayed with me. I remember my fury when I heard what they did and when I began writing Unhallowed Graves that memory was a definite inspiration.

Sometimes my stories come from dreams. I dream about ghosts every night; I never dream about normal things! Some dreams are more graphic than others and sometimes after I have a dream I write it down, in case there is something I can use. Other times, I might read something in the news that ferments an idea.

But I never sit down and plan. And sometimes when an idea comes to me, I’ll scribble and scribble but then I won’t write again for two weeks. And then when the next idea comes, I’ll return to what I have written and I’ll start writing again.

My favourite part of writing is when the characters decide who they want to be and where they want to go and it’s got nothing to do with what I planned or what I imagined, so I just let them go and start typing and they drive me along. I trust my characters implicitly to tell me what to do.

You’re also a publisher. What prompted you to get into publishing?

Me! During the writing course at Warwick, agents would come in every other week and tell us all about publishing and how difficult it is to get into the publishing world, and I knew that because what I was writing wasn’t a known quantity I was unlikely to find an agent or a publisher who would appreciate it and take a leap into the unknown. So I decided to self-publish. The next thing I knew, I was also publishing others. Unfortunately, because I don’t have time to read everything I’m sent, I just select the few that l really like.

And have you any advice for new writers?

At the end of the day, no-one should tell you whether you’re a good writer or a bad writer. As long as that story is inside of you and wants to be told, let it be told because it will not give you any rest until you tell it. And just write it the way you like to write, don’t write it because you think that’s how a commercial story is written. Write it from the heart and don’t write for anyone else’s approval.

Very finally, you always publish your books on June 28th. Is that an Igbo superstition creeping through?!

Unfortunately not! When I was about to publish my first book, and I couldn’t decide upon a date, I just woke up one day, shut my eyes and pointed at the calendar! But the Law of Attraction is a wonderful thing because shortly afterwards, I met a friend I hadn’t seen in forever, and when I asked him to write a review for the back of my book and told him it was being published on June 28th, he said ‘No! That’s my birthday!’ and, later, he gave me the idea for the night market in Unhallowed Graves, the market where the ghosts take over. It’s all down to the universe, so I let the universe direct me.

THE SLEEPLESS is published by Canaan-Star and is out on June 28th and is reviewed here.