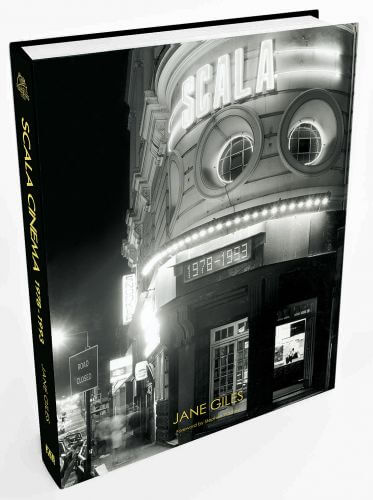

STARBURST readers of certain age and location will have fond memories of London’s Scala Cinema Club, which was a pre-Internet shrine to every cult movie imaginable. Twenty-five years since its last all-nighter, we get nostalgic with programmer-turned-historian, Jane Giles…

The Scala was the UK’s most notorious repertory cinema. Throughout the years of Thatcher and fear-mongering film censorship, it stuck two fingers up to the establishment with a mind-bogglingly eclectic menu, from Hollywood classics to arthouse obscurities to extreme gore. The brainchild of Stephen Woolley (who went on to run Palace Pictures), it was originally at the site of an old concert hall in Tottenham Street, Fitzrovia, before moving three years later to its legendary second home amid the grindhouse squalor of ‘80s King’s Cross.

2018 marks a double anniversary: the 40th birthday of the first Scala show and 25 years since it closed in a storm of controversy. Former Scala Programmer Jane Giles, who was personally prosecuted in the notorious A Clockwork Orange illegal screening case in 1993, has marked this auspicious occasion by writing Scala Cinema 1978-1993, which lavishly showcases every one of the cinema’s famous fold-out monthly programmes, alongside a month-by-month history that lifts the veil on a unique venue that Scala favourite John Waters described as “a country club for criminals and lunatics and people that were high… which is a good way to see movies”.

STARBURST: How did you discover the Scala?

Jane Giles: Well, I was born in 1964 in Crawley, which is near Gatwick Airport so there was not much going on there. When I left school, I fell in with a bunch of boys at Sixth Form College, and they’d go up to London every other weekend on some adventure, usually to see a band like The Cramps or The Birthday Party. My parents were quite strict about what I could and couldn’t do, but for some reason they thought it was OK for their 16-year-old daughter to go off with a bunch of punks from the local school band; they were called the Split Beavers… yeah, I know! One time it was to go an all-nighter at the Scala because the guys had been going there since the Tottenham Street days, where it started in 1978. By this time the Scala had recently moved to King’s Cross. That night I certainly remember Cronenberg being part of it, The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue, Martin, and other things… it was a fantastic all-nighter, I couldn’t believe it. The guys I was with were quite snooty about it, ‘Oh, Tottenham Street was better’, but the minute I saw the King’s Cross cinema I just thought, wow. It was like a sort of gone-wrong version of the beginning of a Walt Disney film where you get the logo of the enchanted castle, a real kind of palace of dreams. I was amazed, I didn’t know such a thing existed. I had discovered repertory cinema at the Duke of York’s in Brighton, but there were such riches at the Scala. Every day there was something that you wanted to see. And the fact that you could stay up all night watching films. VHS was too expensive then, it wasn’t a staple in every student home like it became. So to be able to go and see five films for three quid was an amazing thing. It was a way of educating yourself about film. I really love film and I love music.

You became the programmer for the Scala in 1988 – how did you get the job?

The only thing I was good at school was art, but having done a foundation year, I was told I wasn’t good enough for art school. So in a fit of pique, I applied to study in Reading in 1982, where it was really easy to get in – nobody wanted to go to Reading! I did this thing called a BA in Combined Studies, which is basically film, drama, and art. What I didn’t know was that the film teachers were (acclaimed film theorists) Laura Mulvey, Jim Hillier, Stuart Cosgrove – big names. After that, I did an MA in film and wound up on a BFI placement in Regional Film Theatre Management in Ipswich. I was based at the Corn Exchange there, which is a haunted cinema, by the way! I was there for a year, just learning everything from projection to programming to box office, being paid literally tuppence, but it was fine because I was learning. In the course of that year, I saw a tiny ad the size of a postage stamp in the Guardian with the Scala logo on it that was so familiar to me from going there for several years, and it said ‘Programmer Wanted’ and I thought ‘That’s my job’. I applied for it, Stephen Woolley interviewed me, and I got it. I thought this was the way of the world. I thought work was that you saw your ideal job advertised in the newspaper, you applied for it and you got it, regardless of the fact I was 23 years old. It was effectively my first job – I’d only ever done things like cleaning toilets before that – apart from my training placement. But this was the way that Stephen Woolley was. He was only 19 years old when he set up the Scala. He employed people who were very young; it was a young person’s thing, it needed that energy. Maybe it was the stupidity of young people as well because we took risks that maybe older, more conservative, more conventional industry people wouldn’t take.

How would you describe the audiences at the Scala?

It was always very mixed, it just seemed to be everyone. People dressed to the nines, absolutely in the full Goth regalia, there were very eccentric old-age pensioners as well as very young people who bunked in because they had a burning desire to be there. And the Scala would take their money not out of a cynical desire to get an extra three quid, but because if a young person turned up at the Scala, they were kind of meant to be there – unless they were a rent boy in which case one would keep an eye on them! But young people had a sort of pull towards that place, and the reason why I talk about age is that obviously a lot of the films were 18 certificate, so some people were legally too young to be in the venue.

King’s Cross was very different back then, wasn’t it?

It’s quite posh now, but what was funny for me at the time was that I didn’t really see the vice around me in King’s Cross. I think I was blinkered, as sometimes you are when you’re a young person. I just saw the Scala glowing like a fairy palace in front of me, I didn’t see the prostitutes and the junkies. But by the end, it was very bad. By 1993, we had people shitting on the doorstep. There were crack dealers. There was a knife fight one night where the dealers burst through the doors to try and take refuge in the foyer. It was awful by that point, so bad. It was disgraceful what happened to King’s Cross in the name of re-development. They had to bring it really low in order to get all of the small businesses out. It was strategic and it was horrible.

The Scala prided itself in presenting hard-to-find movies uncut where at all possible. What were the challenges in getting this material onto the screen?

Pretty much everything at this time was on 35mm film or 16mm film, and this was actually really liberating because there were big collections of 16mm material. One of the unique things about the Scala was that it had an amazing 16mm projector fitted with a Xenon lamp, so it was almost as good as 35mm. The 16mm film catalogues were very, very rich both with Hollywood movies but also the highways and byways, because film societies and the educational sector were very strong before home video, so 16mm prints would routinely be made for a really interesting range of material. And 16mm prints tended not to get worn out in the way that 35mm did, and it was a smaller gauge so it was smaller to store. There was an organisation called FilmBank, which was set up by the studios to handle their non-theatrical 16mm collections. So one of the things that the Scala did that was not strictly ‘regular’ was to book 16mm film prints into a commercial cinema. We stood behind our ‘club membership’ status to argue that we weren’t commercial in the way of the Odeons and chain cinemas. It was a grey area to say the least, and mostly distributors turned a blind eye to it because nobody really cared so long as we paid our bills, which we did.

In the late ‘80s, the Scala hosted the Shock Around the Clock all-night horror festival, organised by former STARBURST writer Alan Jones, which was the predecessor to FrightFest. What are your memories of it?

Shock Around the Clock was intended to be a one-off event, as Alan told me, in 1987. And it was such a rip-roaring success that it was repeated in 1988 and ‘89. My first experience of it was in 1989 and I was amazed by it. It was not unusual for the cinema to be completely full, but what was unusual about Shock Around the Clock was that it was the first time I’d seen such a vocal audience. The audience could usually be quite noisy, interacting with the films, but with Shock Around the Clock it was a really special atmosphere. It also seemed to be very hot! There was literally sweat running down the walls, people passed out on the floor… I think it was a sense of people being so happy just to be there. Tickets were really in demand so people felt a real sense of achievement even getting into the building and being able to watch 20 hours of film, or whatever it was. There were horror films and there was gore, but it was not a reverent environment. People would cheer and whoop and make signs of distress, so it wasn’t an uncritical audience.

The Scala pulled off some great coups, such the being only place to see David Lynch’s Eraserhead in the UK upon initial release…

Oh yes, I’d completely forgotten that and it was a surprise to me when I did the research to find that it opened exclusively at the Scala. Critics really struggled with Eraserhead, they couldn’t find the language. It genuinely was something really different. The Scala programmed a whole ‘Cinema of the Bizarre’ season to contextualise it and to help prepare the audience. It included double bills of Nosferatu and Vampyr for a week before Eraserhead. But then, when it was into its run, to put on the Devo music film with it (In The Beginning Was the End: The Truth About De-Evolution), that really helped, because it was kind of a post-punk rock, New Wave audience. One of the brilliant things that Stephen Woolley did in the early days of the Scala was to make that music connection, because he was a huge punk fan. By inviting bands in, by working with Tony Wilson of Factory Records and getting bands like Throbbing Gristle, New Order, and Spandau Ballet in, he made that connection with the music crowd. The music press was very strong then. You were always at the mercy of Time Out, there was no other way of marketing apart from through the print media so they gave a different angle, a different audience, and that was something that continued at the Scala all the way through to the end. When I was there, we had people like Nick Cave, Lydia Lunch, and Gallon Drunk. There were lots of music films shown as well and by the end, there was the ‘The Grey Area’, which was programmed by Chris Bohn from Wire magazine, showing Industrial Noise movies.

1981 Scala by David Babsky

The press often cites the famous A Clockwork Orange breach-of-copyright legal case as the reason the Scala closed down in 1993, but that wasn’t the real story was it?

The Scala moved into the King’s Cross cinema in 1981 on a 12-year lease. So in June 1993, the lease ran out and the landlord wanted to triple the rent. But Palace Pictures had gone bankrupt in 1992 and with Steve Woolley and Nick Powell being directors of the Scala as well as Palace, we couldn’t raise the finance to re-develop the cinema in order to pay the landlord’s elevated rent. Plus, there was still a compulsory purchase order on the building relating to the high-speed rail link. So it was those factors that ultimately conspired to end it. The thing with A Clockwork Orange is the legend that gets printed, but if the lease hadn’t expired, the Scala wouldn’t have closed down in 1993.

The book tells the story of the Scala as a historical narrative but also with a vast number of photographs and by reproducing all of the famous photo montage fold-out programmes. How did the book concept evolve?

The Scala programme was based on the American ‘Calendar Houses’ such as the NuArt in LA and the Roxie cinema in San Francisco. These programmes washed up in London in the hands of Stephen Woolley so he gave them to the designer and said ‘do this’. The Scala had been experimenting in its first year with different formats, but nothing really captured it until that concept. Suddenly, everything made sense, it was an absolute work of genius and people pinned them up on their walls, they collected them. I always wanted to write a cultural history and film history of the Scala. Then I met Harvey Fenton of FAB Press and he’d always wanted to publish a book of the programmes. I thought this was an impossibility because it’s very expensive and very difficult to do highly illustrated books; printing is very expensive. But Harvey had this mad vision to reproduce them legibly, so we had this huge conversation on what the book could be like and we just basically put my idea for a history book and his idea for a book of programmes together and did both. It’s huge, it’s enormous – as big as your forearm at least. It flattened me, this book. It’s like a sort of Victorian folly to have created it. Nobody has ever done this: to gather every single programme from a single venue. It was made possible by the Internet. We knew that crowdfunding was an option because Harvey had just done that with an update of Stephen Thrower’s epic Lucio Fulci compendium Beyond Terror, releasing it as a very lavish edition. I knew the Scala had a fan base because I’d set up a Facebook group for former staff and friends. People were swapping memories but also, crucially, swapping materials and photographs. So it suddenly became possible to gather all those things together and create this book. We had some help from famous people, like Jonathan Ross, in the film industry who put some money towards the production costs, which was great but it’s been a really foolhardy enterprise that has nearly bankrupted Harvey and nearly crippled me!

Arriving at the Scala back then, it always felt very exciting, almost ritualistic, signing up to your ‘membership’ status for the evening…

Absolutely right, there was something ritualistic about signing in and a sense of privilege to being a member of the Scala. You had the NFT or Everyman Cinema-type people who kind of looked down on us, but it was somewhere that anyone could become a member, whether you were a boy in an anorak or whether you were Boy George, literally. All of those people were members, it was really something that I think doesn’t exist anymore. It was a club that anyone could join, but not everyone wanted to.

Scala Cinema 1978-1993 is released by FAB Press on September 26th and is available to pre-order here. For information on programming and events UK-wide in September 2018 visit scalarama.com.