When I finished Volume II, I was so sure that this novel would end in some epic battle, be it Norrell v. Strange or Norrell and Strange v. the gentleman with the thistle-down hair, and I imagined sitting down to write this review and spending most of the time gloating over how right I was. I have, after all, spent three months reading and analyzing this book within an inch of its papery life.

I was right…if the word “right” looks startlingly like the word “wrong”.

My great fallacy, I think, is that for all that this is a book published in the twenty-first century, I forgot the fact that it is written about—and like—a book from the 19th century. Massive climactic battles are not a hallmark of fiction from the era. Instead it’s introspection, and while I can’t deny that I am a tad disappointed that there was no huge fight as I had long assumed there would be, it doesn’t make me love the novel any less.

And oh do I love this novel.

When we last left off, Strange had gone to war and Norrell had squirreled away more magical books and then, having diverged so much from the opinions of his teacher, Strange abandoned his position as a pupil under Norrell’s tutelage. All the while, the enchantments that had ensnared Stephen Black and Lady Pole wound themselves tighter, and Arabella Strange, poor, sweet, loved Arabella, became the prey of the gentleman with the thistle-down hair. In Volume III we see the aftermath of the gentleman’s attentions to Mrs Strange in the havoc it wreaks with her husband. I’ve discussed Arabella and Strange’s relationship before, how typically 19th century it is all distance and decorum. Neither reader nor other characters could believe that Strange cared anything for his wife at all. Suffice it to say that Volume III does everything to dispel this notion, and does it with such skill that my heart ached for them. And how can’t it, with lines like: “‘There is an ache here.’ [Strange] tapped his heart. ‘And something hot and hard inside here.’ He tapped his forehead. ‘But half an hour’s conversation with Arabella would put both right, I am sure.’” Strange’s loss is written so wonderfully that it is able to do what all good literature should do: elicit a visceral reaction from its readers. Clarke uses both words and plot to accomplish this, because it’s not just that Arabella is gone and Strange is distraught, it’s how Strange communicates his distress that makes it so powerful. The above passage is sad, but it’s made even more so in context: Strange has been trying to purposely make himself go mad in order to better perform magic and to, ultimately, summon a faerie. At this moment, he is so mad that he thinks he’s Norrell’s friend Lascelles! As far as he’s concerned, he’s another person altogether, and yet he still thinks about his wife, and her absence is felt so acutely that it’s physical. This technique makes Strange’s narrative a powerful one, and gives weight to both his actions and to other character’s reactions to it.

It is this relationship that has always been one of the defining differences between Norrell and Strange, a difference that is made even more clear after she falls to the gentleman with the thistle-down hair. In fact, I would go so far as to say that Strange’s relationship with Arabella pretty much sums up his and Norrell’s differences of character. Strange is emotional, youthful (in every sense of the word), bold and open-minded; Norrell is unemotional, old, cruel, and close-minded. Norrell says early on in the novel that magicians have no business being married, as it only serves as a distraction from what is most important: learning magic. Emotional attachments are useless to Norrell, which becomes more and more obvious as the novel progresses, and horribly so. You would think that after having such a loyal, caring person like Childermas as a companion (while technically a servant, Childermass hardly holds to the role), Norrell would have some attachment to him. You would think that Norrell would care when he gets hurt and would trust his advice and, generally, not act like such an ungrateful jackass. But Norrell doesn’t have an attachment to anything except his books, and this sterility of emotion is detrimental to him. People need social interaction, and until he moved to London it appears that Norrell received little of that. A decade later, his improved (although still limited) social interaction appears to have done nothing for him. For all that Norrell is extremely manipulative, he’s not the best judge of people, taking what they say at face value and never considering that maybe, with some people, he shouldn’t. This sterility of emotion is not only what keeps Norrell from growing as a character, but it also keeps him from growing as a magician. Norrell is certain that marriage—emotional attachment—is a weakness, but it is while married and thus steeped in a heavily emotional relationship that Strange makes some amazing magical discoveries. He truly becomes, I think, the Greatest Magician of Their Age, and not because he’s studied hard and conned the competition, but because he loves, and no matter what love is more powerful than intellect.

It is this love which completes the comparison of Strange to Merlin that Clarke began in Volume II, when the Duke of Wellington gave Strange the nickname of Merlin when they were fighting in Spain. In many versions of Arthurian myth, Merlin’s death is always tied to a woman: Nimuë (aka Viviane, or the Lady of the Lake, depending on the work). According to the myth, Nimuë seduces Merlin and uses an enchantment (often times magic that Merlin has taught her himself) to trap him in a tree, a stone, or a cave. Sometimes she is willfully malicious, sometimes contrite, and it’s the latter that links most closely with Arabella, the novel’s Nimuë figure. Like Merlin, Strange finds himself put under an enchantment, with Arabella as an indirect cause as she doesn’t perform the enchantment herself. In fact, she doesn’t perform any magic, nor does any other woman. A female magician is mentioned in having existed in the novel’s past, and we are told that some women do take an interest in magic after Norrell and Strange resuscitate English magic (one such woman appears at the end of the novel), but of the primary women in the novel, Arabella Strange and Lady Pole and (in Volume III) Flora and Aunt Greysteel, none of them show any interest in practicing magic themselves. However, in a way this does tie Arabella closer to her Arthurian counterpart: Nimuë’s exposure to magic in some versions is through Merlin, who teaches her magic; similarly Arabella’s exposure to magic is through her husband, the Merlin figure of the novel. Arabella’s not having performed the enchantment turns her into a more sympathetic character than Nimuë, who even in her contrition still cursed Merlin by her own hand. It is also what makes Arabella and Strange’s relationship even more tragic, especially when you take into account that this was Merlin’s death.

I’ll leave it to you, readers, to find out for yourselves whether or not this was Strange’s death as well.

Overall, this is a fantastic novel. Clarke has made her alternate history incredibly rich, so much so that despite three reviews I have barely scratched the surface. The plot is well-crafted, everything interconnected and no character forgotten. From my own experience writing prose, I know how difficult it can be keeping track of a large cast, and I am extremely impressed that she is able to do so with such skill. The characters are also well-rounded, complex and flawed and wonderfully human. They feel so real sometimes, and as I said previously it is a hallmark of good fiction when a writer is able to elicit a visceral reaction from their readers. There were times when characters—particularly Norrell—frustrated me so much that I swore out loud and had to suppress the urge to toss the book across the room. There were also times, in the third volume especially, when I could feel myself hovering on the edge of tears and in fact did end up crying, so very heartsick. I know some might think it silly to get so wound up by fictional characters, but isn’t that what storytelling is supposed to do? For centuries it has been a tool used to inspire, to comfort, to warn, to make someone laugh; to have the message within the story resonate so much with its audience that they will go away with the desire to apply its teachings to their lives and to the world around them. This is why stories last so long, why thousands of years later we are still reading The Iliad and why Shakespeare plays still sell out theatre seats: stories leave an impression on our souls.

Of course, it’s not a perfect novel. I don’t think those exist, even with the Pulitzer Prize winners. Clarke’s use of antiquated spelling such as “chuse” instead of “choose” and “shewed” instead of “showed” in order to more firmly place the novel as something belonging to the 19th century still, even after a thousand pages, continued to trip me up. They are used far too sparingly, I think, allowing you no chance to grow accustomed to them, and instead of pulling me deeper into the narrative every rare occasion that I saw them only served to violently eject me from the text and remind me that that’s all it was—words. It made the novel appear self-conscious, and frankly I think the book would have been better served if she had stuck with the modern spellings that she uses for the other 99% of the novel.

What also proved frustrating were the footnotes. I’ve said before that the footnotes can be appreciated in hindsight. They make Clarke’s alternate history richer, more fleshed out and real, but there were many times when I was speeding through the action and suddenly there was a footnote, interrupting my momentum and keeping me from the building narrative, sometimes for pages, and I know much swearing occurred. As a writer, I can understand why Clarke uses them; she has spent so much time constructing a detailed world and doesn’t want to see her hard work go to waste, and the book is so much a history text that footnotes serve to emphasize and support this structure. As a reader, however, for all the more wonderful things that the footnotes taught me about the novel’s universe, the fact that it kept distracting me from the narrative I was most invested in proved so annoying that there were times when I considered ignoring the footnotes altogether.

I didn’t, and as I said, in hindsight I know that was a good thing to do.

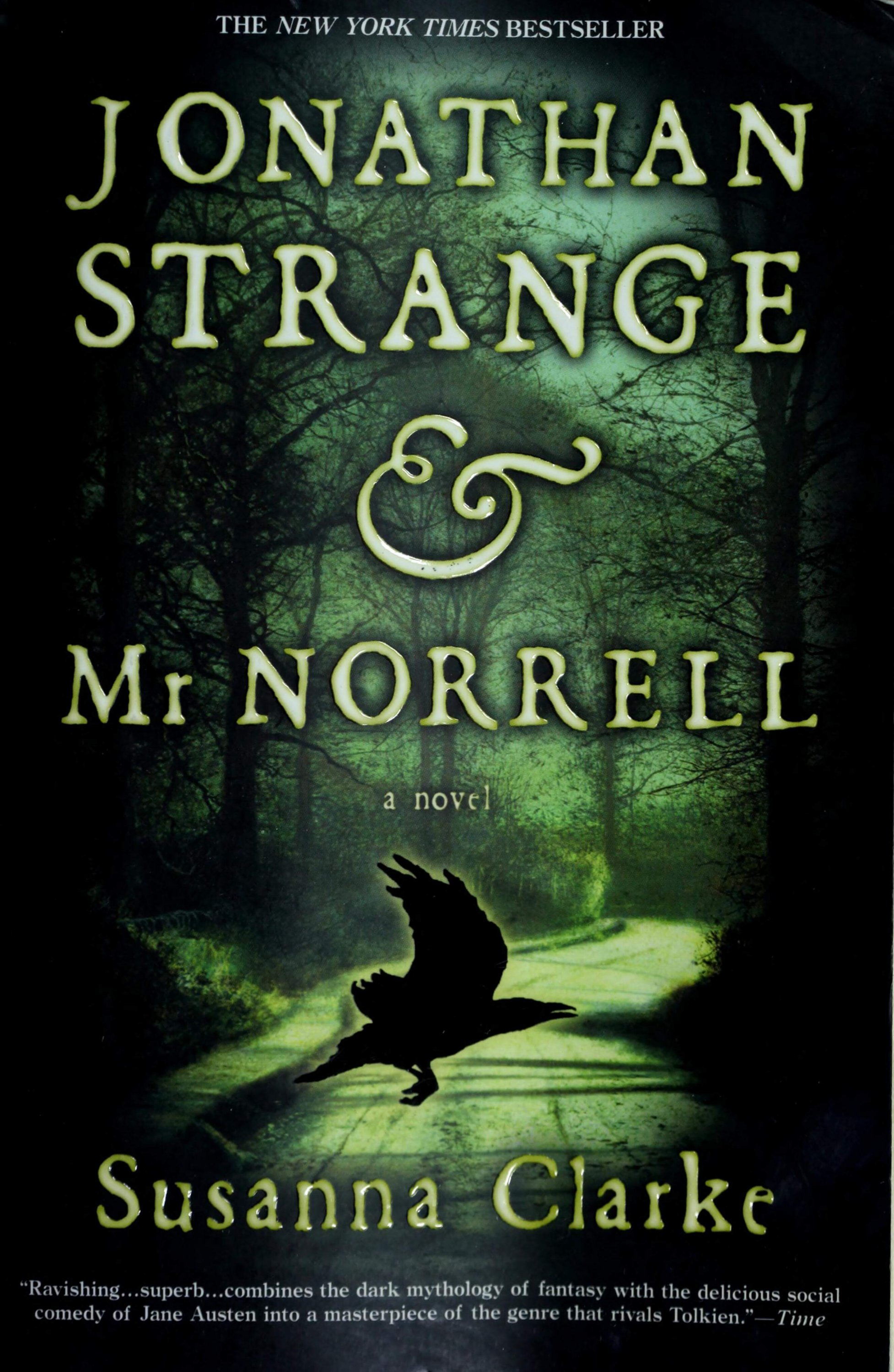

Quite a while ago, reviews and reviews ago, I commented on the presence of genre fiction outside of the genre fiction sections in bookshops. Books like Slaughterhouse Five and 1984 aren’t in the same department as Terry Pratchett, regardless of the presence of dystopian futures and time travel which link them. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, for all that it is clearly fantasy, was found months ago among the literary fiction, in the same section of Waterstone’s as Margaret Atwood and Angela Carter. When I purchased it I wondered why it was there, and even after reading it I’m still wondering. Is it because it’s an alternate history—alternate historical fiction—and as other works of historical fiction are shelved outside of the genre fiction area, Clarke’s novel went the same way? Is it because it was shortlisted for an award (the Whitbread First Novel Award)? But then that assumes that genre fiction is only literary when it is award-winning, and many sci-fi and fantasy books have won Hugo Awards (among others); is it, then, only non-genre fiction awards that make it literary? It sounds incredibly snobbish to assume that just because it was acknowledged by something open to works of multiple genres that Clarke’s book has been somehow…elevated. Because that implies, erroneously, that genre fiction is less important than literary fiction, and I’m sure you know now how little I believe that. To be honest, I can’t think of a good reason why Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell wasn’t with the rest of the fantasy novels, but I doubt that it was a quirk of the bookshop staff.

I wholeheartedly recommend this book. It is intricately and carefully constructed, so much so that you can see how much effort the author put into it. The characters are real and the plot is engaging, and for all of its flaws it is a worthwhile read. It’s a commitment of course, due to its length and depth, but like many things it’s worth the time you decide to give it.

And with all of the bits I’ve left out, aren’t you just dying to find out the rest of the story?

[Article originally published in October 2011]