Ah, telephemera… those shows whose stay with us was tantalisingly brief, snatched away before their time, and sometimes with good cause. They hit the schedules alongside established shows, hoping for a long run, but it’s not always to be, and for every Street Hawk there’s two Manimals. But here at STARBURST we celebrate their existence and mourn their departure, drilling down into the new season’s entertainment with equal opportunities square eyes… these are The Telephemera Years!

1976-77

For some reason – the US’s failure in Vietnam is often blamed – the American public could not get enough of the rock ‘n’ roll era in the 1970s, a point never more heavily underlined than with the success of Grease in 1978. It started before that, of course, with George Lucas’s American Graffiti giving birth to the Fonz on TV. It was almost as if the whole country wanted to forget the last decade or so and that Happy Days was the number one show for 1976-77 is no surprise. That spin-off Laverne & Shirley is number two is perhaps a little more surprising, but there’s Korean War comedy M*A*S*H at number four to ram things home. Outside this yearning for the past but also making headway in the TV ratings were telefantastic Jiggle TV mainstays Charlie’s Angels and The Bionic Woman, as well as The Six Million Dollar Man, Baretta, and Hawaii Five-O; if there was somewhere the US TV viewing audience wanted to be in 1976 it was not the 1976 outside their door.

Several big shows bade their farewells this season with The Streets of San Francisco finally running out of road, the departure of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Phyllis setting women’s emancipation back a few years, and Sanford and Son a victim of America’s disposable Capitalism. Coming in to take their places were interfering coroner Quincy, bear-worrier Grizzly Adams, and Roots, the first of the blockbuster mini-series that gave schoolchildren everywhere license to say Kunta Kinte. But those were all hit shows – what about those shows that didn’t hang around, that didn’t make much of an impact on the 1976 public? This is the story of four failed TV shows…

Lanigan’s Rabbi (NBC): The ongoing search to find that unique angle on the detective genre has touched on some strange corers, with blind detectives, fat detectives, woman detectives, and more all given a shake of the stick. In 1976, however, NBC decided to take inspiration from the man upstairs and bring a man of God to the table, foisting Lanigan’s Rabbi on a nation of Jew-curious gentiles.

Based on a series of books by Harry Kemelman, a former New England college professor whose first hit novel starred a New England college professor as its gumshoe principal. He hit gold with his series of novels featuring Rabbi David Small, beginning with 1964’s Friday the Rabbi Slept Late which saw him use Talmudic wisdom to find the real culprit of a crime it appeared he’d committed. Kemelman’s books were heavy on the traditions of conservative Judaism, often bringing Small into conflict with less observant types, although Kemelman seldom comes down on one side or the other.

After Stuart Margolin had played him in the pilot, Bruce Solomon stepped into the Rabbi’s shoes, fresh off over a hundred episodes of satirical soap opera Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, and he was joined in the main cast by The Honeymooners’ Art Carney as Paul Lanigan, local police chief and a practising Catholic with whom the Rabbi often discusses religion between cases. After that pilot film – an adaptation of Friday the Rabbi Slept Late – was a hit, the show continued as a series of ninety-minute films, all written by Don Mankiewicz, who’d adapted Ironside from that series of novels.

“Corpse of the Year” aired in January 1977, followed by three more films – “The Cadaver in the Clutter,” “Say It Ain’t So, Chief,” and “In Hot Weather, the Crime Rate Soars” – in March and April as part of the NC Sunday Night Mystery Movie wheel format, replacing Quincy, ME, which had been spun off into its own series. There would be no spin-off for Lanigan’s Rabbi, though, as NBC discontinued the format and cancelled the show, alongside McCloud and McMillan & Wife, although Columbo was given one more series before it, too, got the axe.

Mr T & Tina (ABC): A spin-off of popular remedial education comedy Welcome Back, Kotter, Mr T and Tina was one of the first shows on American TV to have an Asian lead, admittedly one born and raised in California. Pat Morita – for it is he – had made a career out of guest appearances as the token Asian character on shows such as McCloud, Columbo, The Odd Couple, and Sanford and Son, and was starring as Arnold on Happy Days when he got the call from Mr T creator James Komack.

Morita’s character of Taro Takahashi had appeared in Kotter’s season two opener “Careers Day,” where he offered Gabe Kaplan’s character a job with his company at three times his school salary, and reaction to Morita from viewers was enough that he was brought back for a turn of his own just two days later. Of course, TV doesn’t work like that but who would I to be to suggest that his Kotter appearance was nothing but a cynical marketing ploy?

In Mr T and Tina, Takahashi is a widowed inventor sent to Chicago to run a new branch of his family company, Moyati Industries. To look after his children, he employs madcap free-spirit Tina Kelly as a nanny and it doesn‘t take long for her liberal ways to clash with his uptight Japanese traditions. Of course, that’s where the comedy – and the possible “Will they? Won’t they?” – lay, and Arnold was written out of Happy Days in anticipation of the show being a hit.

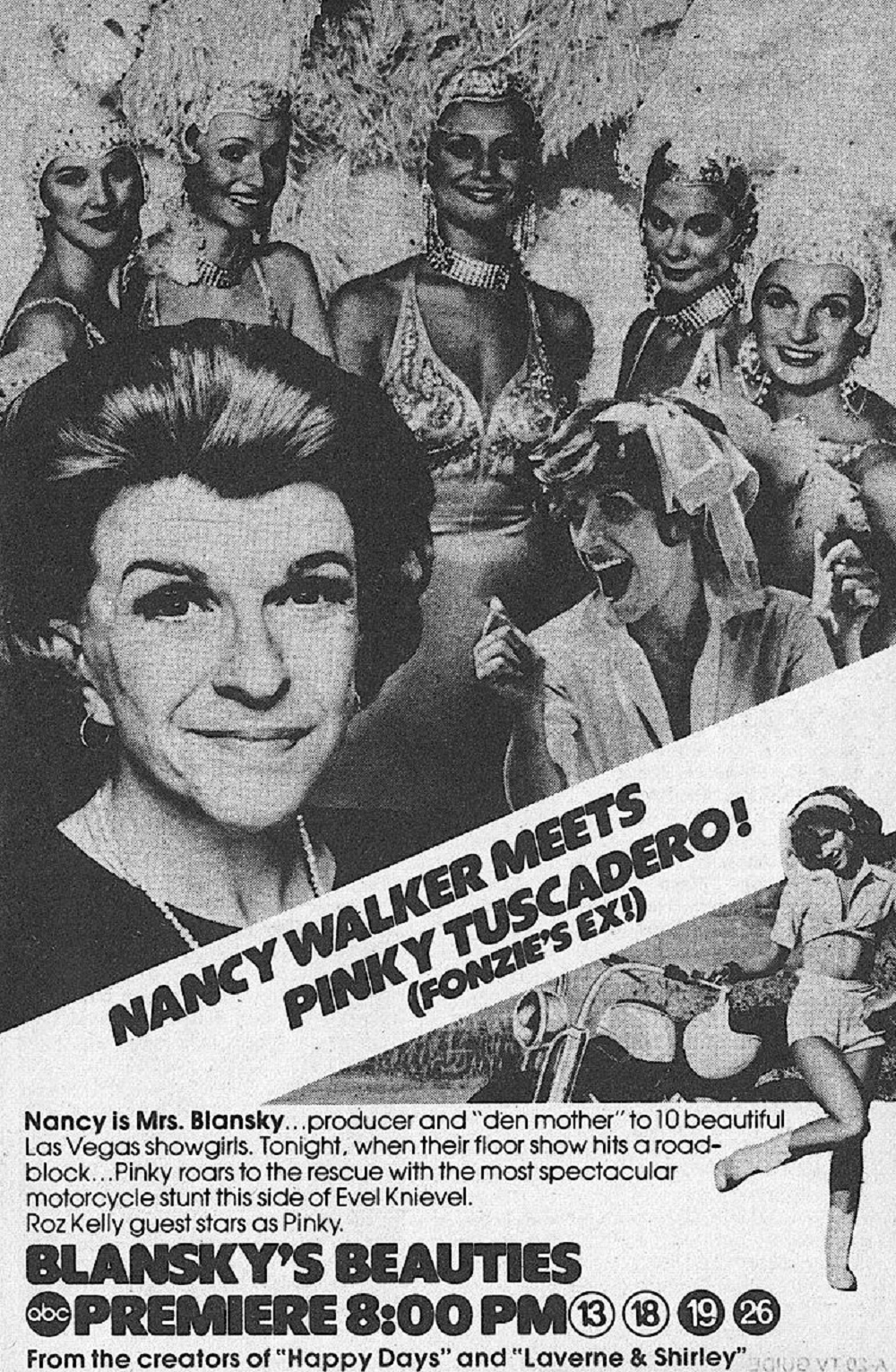

Unfortunately, even after the pilot was re-written eight times, viewers hated the show, even if they loved Morita, and the show lasted just five episodes, with Kotter writer Mark Evanier later claiming that the decision had been made to cancel the show before the pilot even aired. Morita went back to being Arnold on short-lived Happy Days spin-off Blansky’s Beauties, returning to the main show for its final two seasons in 1982. Luckily, writers hadn’t taken Tom Bosley’s suggestion that Arnold be killed off by “some crazy kamakazi (sic) pilot…”

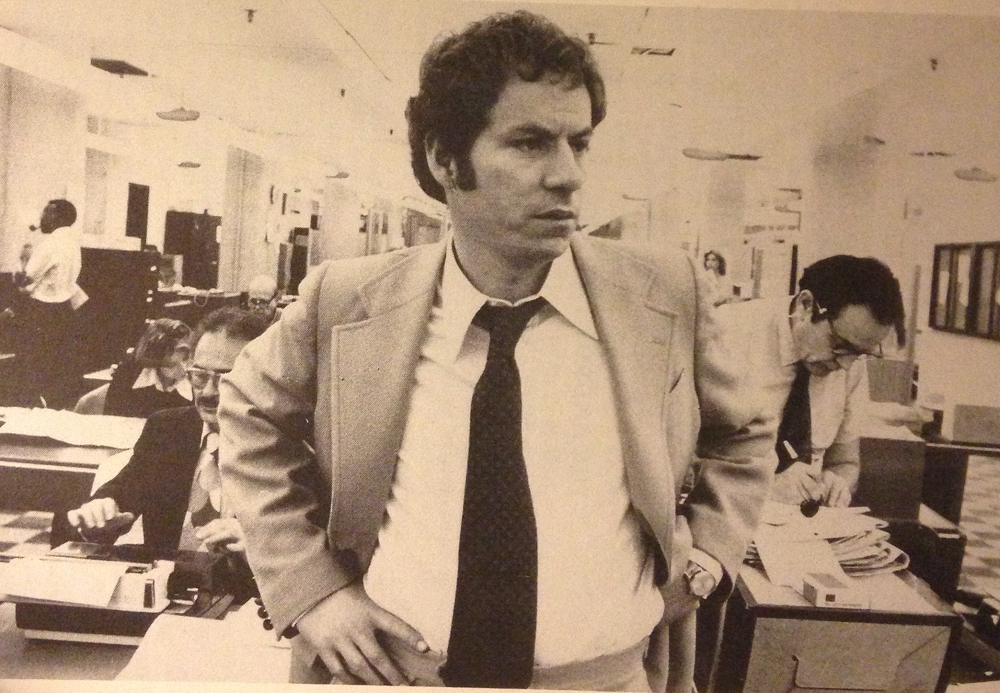

The Andros Targets (CBS): In the wake of Woodward and Bernstein breaking the Watergate scandal, crusading newspaper reporters were all the rage in the mid-1970s, with All the President’s Men -starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein themselves – nominated for eight Oscars alone. TV was quick to pick up on the craze, with Lou Grant blazing a trail on The Mary Tyler Moore Show for CBS, and it was the Tiffany Network that also dipped its toes into more dramatic fare with The Andros Targets.

James Sutorious, with just medical drama The Doctors of any note on his résumé, was Mike Andros, an investigative reporter for the New York Forum specialising in tackling corruption and uncovering miscarriages of justice. With the aid of young assistant Sandi Farrell (newcomer Pamela Reed), Andros joined a list of people doing the police jobs for them, alongside coroner Quincy and lawyer Petrocelli.

Creator Jerome Coopersmith, a former writer on Hawaii Five-O and The Streets of San Francisco and probably best known for Sherlock Holmes musical Baker Street, based Andros on Nicholas Gage, a journalist for the Wall Street Journal and New York Times who wrote two bestselling books about his investigations into the Mafia. Gage is given a credit as “journalistic consultant” but whether he ever had to investigate cases involving the pornography-linked death of a young stress, a doctor administering illegal amphetamines, or a brainwashing religious cult is unknown. Andros, did, though, in episodes one, four, and six.

The Andros Targets debuted in January 1977 as a replacement for the cancelled Executive Suite on Monday nights but struggled to find a consistent audience opposite football and movie presentations on the rival networks, ending its thirteen-episode run in May with an average rating that placed it eighty-fourth for the year. There was no second season and Lou Grant was given his own eponymous show a few months later instead.

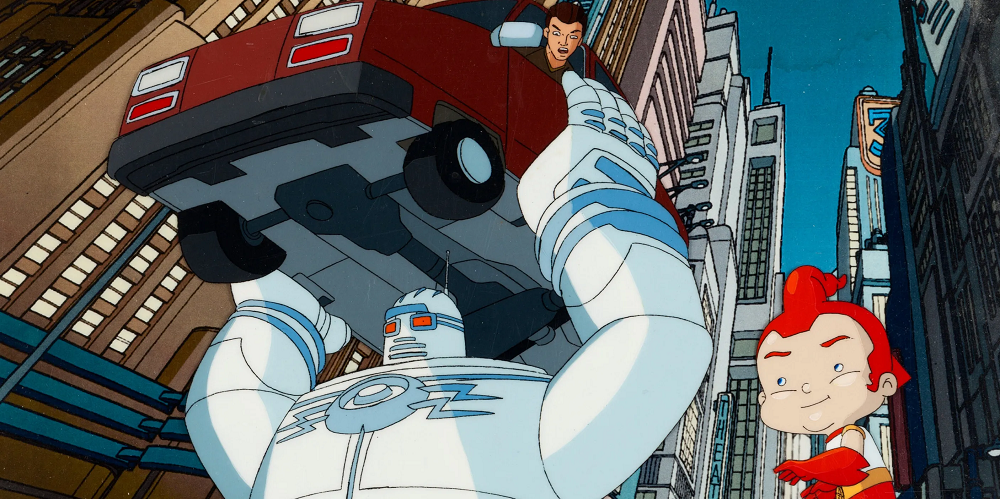

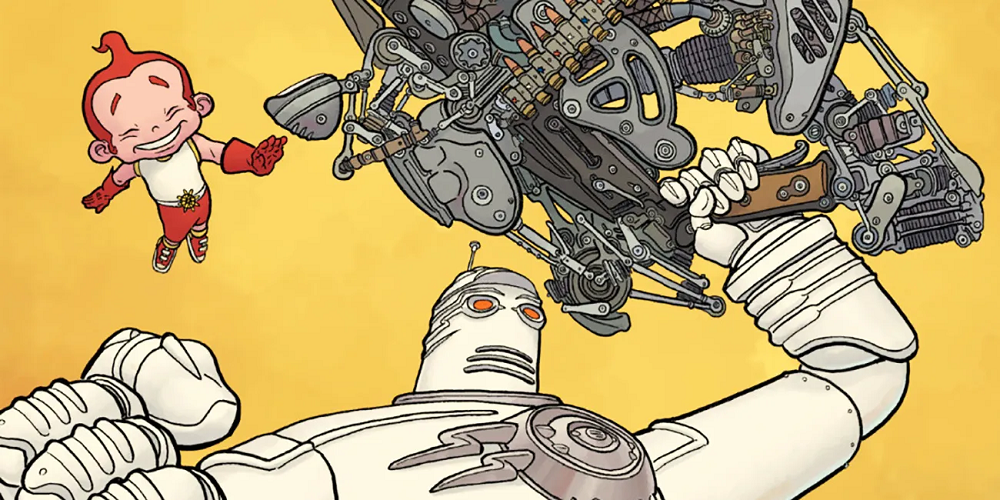

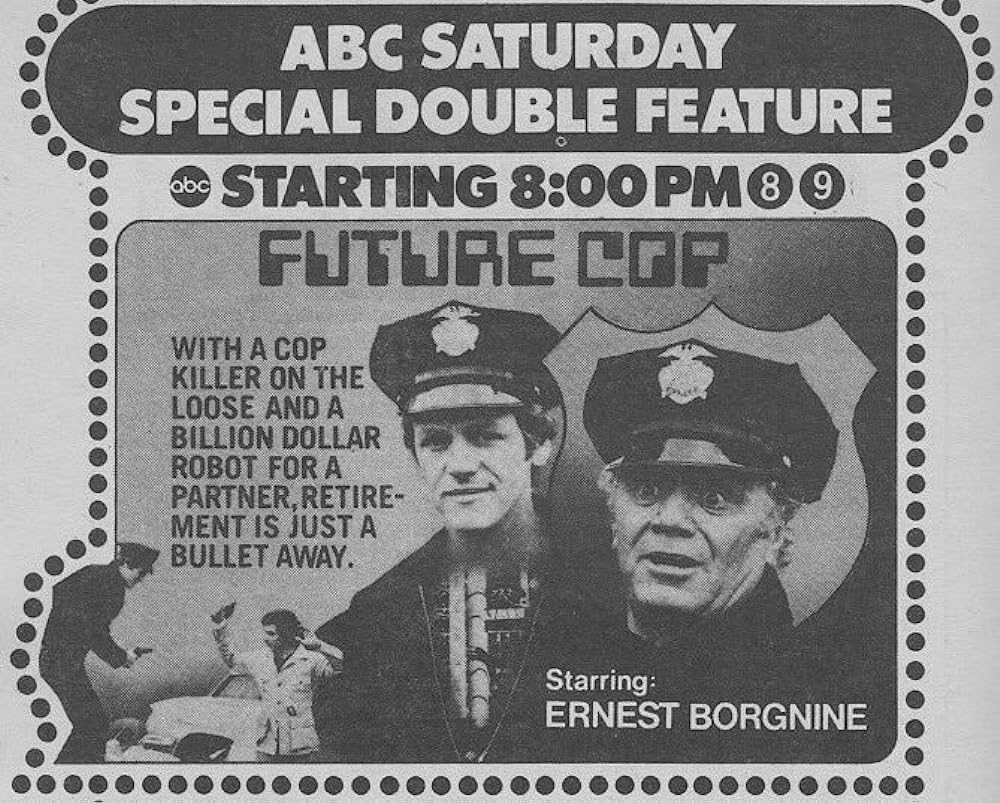

Future Cop (ABC): Given that Holmes &Yoyo had lasted just thirteen episodes on ABC before being cancelled in December 1976, quite why the network decided to go ahead with Future Cop is anyone’s guess. Both shows featured uptight policemen saddled with robot partners prone to malfunctioning, although the pilot of Future Cop – shown as a TV movie – predated the other show by a few months so who knows what was going on at ABC that year!

Anyway, the Future Cop pilot starred Ernest Borgnine and John Amos as veteran patrolmen Joe Cleaver and Bill Bundy, who are given a new rookie partner in the shape of handsome young John Haven. Haven, though, is more than he seems – he’s possibly the future of law enforcement! – and the two crusty old flatfoots need to learn to embrace the future even as they impart valuable life lessons to their new android pal.

Future Cop was less slapstick than Holmes & Yoyo and not without pathos: it must have been this that convinced ABC that it could succeed where the earlier show had failed and a full series began in March 1977, in the same Saturday night slot as H&Y. The first episode saw Haven go undercover as a boxer to uncover a crooked betting operation and subsequent adventures saw the odd trio – although it was very clearly the Borgnine and Shannon show – tackle revolutionaries, drug pushers, and kidnappers.

Although viewers gave Future Cop even shorter shrift than Holmes & Yoyo, two people who did notice the show were sci-fi writers Harlan Ellison and Ben Bova, who had written a short story called “Brillo” in 1970 about a policeman and his new robot partner, later adapting their story as a pitch for a TV show. The pair claimed significant similarities between their story and Future Cop and launched legal action, finally being awarded over $300,000 in damages when the lawsuit was settled in 1980.

In the meantime, ABC employed writers John T Dugan, Dawning Forsyth, and John Anthony Mulhall to retool the concept as Cops and Robin, shooting a pilot with pretty much the same cast in 1978. This was aired as a TV movie in March 1978 although, this time at least, more sensible heads prevailed and there was no subsequent series for Borgnine’s cantankerous old cop with a heart and Shannon’s synthetic rookie (also with a heart).

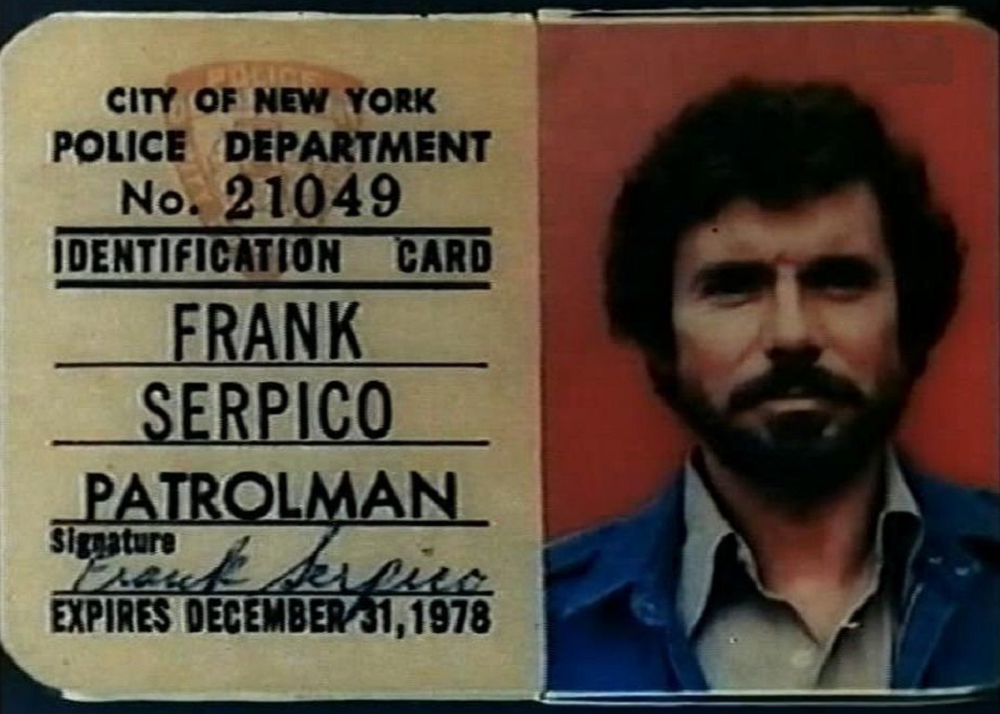

Serpico (NBC): Al Pacino was nominated for an Oscar for his 1973 performance as Frank Serpico, a real-life New York cop shot in the face after blowing the whistle on police corruption, possibly at the orders of his fellow officers. Sidney Lumet’s movie was a blockbuster hit, turning Peter Maas’s book on which it was based into a bestseller but Serpico’s story – he retired in 1972 with a begrudgingly given Medal of Honor – was a one and done, and Pacino and Maas turned to other projects.

Nothing is ever truly done in television, though, and the success of Serpico’s debut on terrestrial TV in 1975 set wheels in motion at NBC, where Police Woman creator Robert L Collins was tasked with developing a series based on Frank Serpico’s general demeanour, if not his real-life exploits. A pilot film – Serpico: The Deadly Game – aired in April 1976 and was well-received enough that a full series was greenlit, debuting on Friday nights in September 1976, with The Rockford Files as a lead-in.

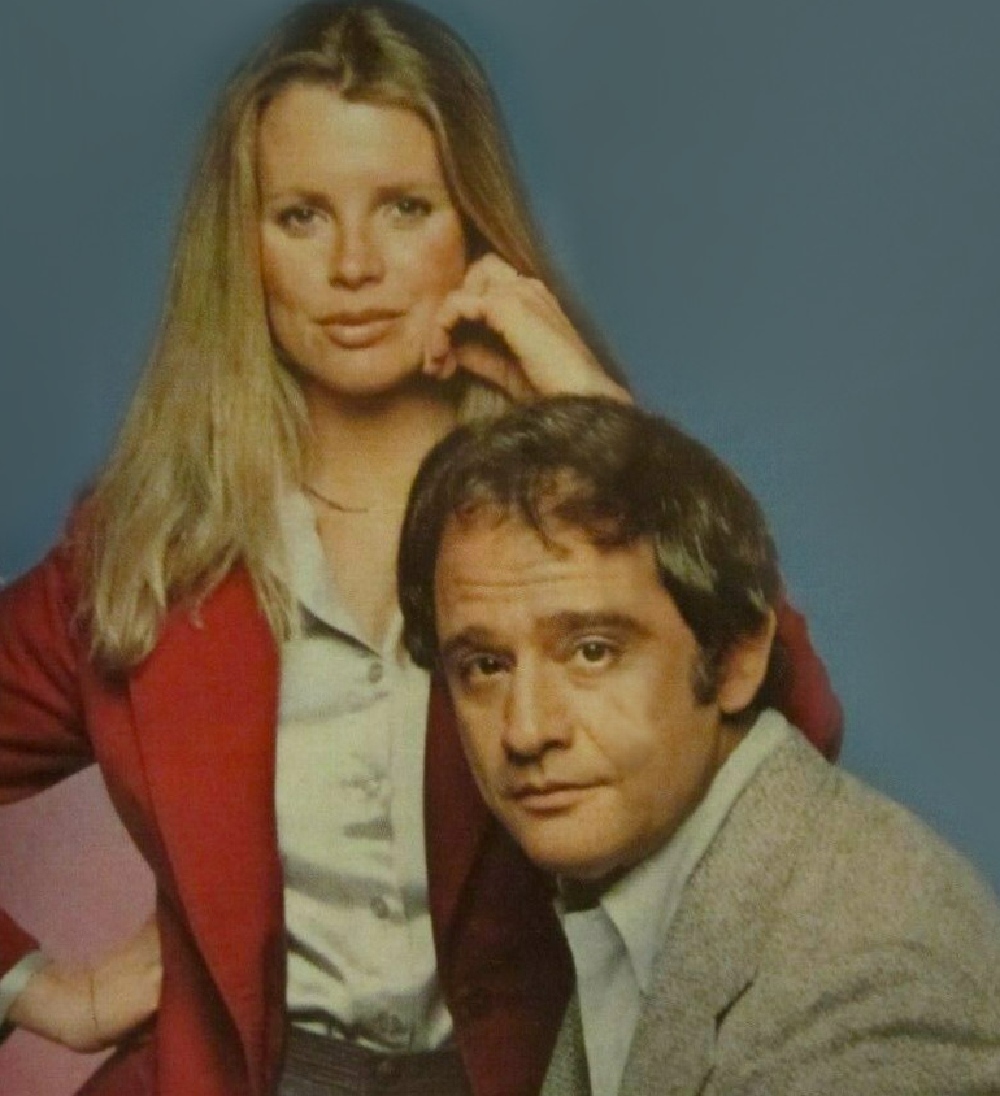

Playing Frank Serpico in both the pilot and the subsequent series was David Birney, a stage actor whose TV résumé featured a ton of guest appearances and one lead role, the 1972 sitcom Bridget Loves Bernie with Meredith Baxter. Birney was a decent actor but also looked a little bit like Pacino in a certain light, and was given solid back-up from Tom Atkins as his boss, Lieutenant Sullivan, the only other regular cast member in a show that featured its principal mostly undercover in a different scenario each week.

Soviet defectors, loan sharks, crooked union bosses, and more crossed Serpico’s desk but viewers just didn’t buy into the continuation of his story, even with veteran directors Collins, Reza Badayi, and Paul Stanley on board. After just fifteen episodes, NBC pulled the plug, replacing the show with Quincy, ME, and it would be six years before Birney found another starring role, as Dr Ben Samuels in the first season of St Elsewhere. As for Frank Serpico himself, he’s still alive and still speaking out about police corruption but not getting shot in the face for it.

Next time on The Telephemera Years: More of 1976’s misses, including another Happy Days spin-off and Playboy‘s favourite rock star!

Check out our other Telephemera articles:

The Telephemera Years: pre-1965 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1966 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1967 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1968 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1969 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1970 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1971 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1973 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1974 (part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

The Telephemera Years: 1975 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1977 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1978 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1980 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1981 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1982 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1983 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1984 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1986 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1987 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1989 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1990 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1992 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1995 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1997 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1998 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 1999 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2000 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2002 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2003 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2005 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2006 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: 2008 (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Telephemera Years: O Canada! (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

Titans of Telephemera: Irwin Allen

Titans of Telephemera: Stephen J Cannell (part 1, 2, 3, 4)

Titans of Telephemera: DIC (part 1, 2)

Titans of Telephemera: Hanna-Barbera (part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Titans of Telephemera: Kenneth Johnson

Titans of Telephemera: Sid & Marty Krofft

Titans of Telephemera: Glen A Larson (part 1, 2, 3, 4)